Summary

On March 13, 2018, we published a blog describing a new Android malware family we discovered and called “HenBox” based on metadata found in most of the malicious apps. HenBox apps masquerade as others such as VPN apps, and Android system apps; some apps carry legitimate versions of other apps which they drop and install as a decoy technique. While some of legitimate apps HenBox uses as decoys can be found on Google Play, HenBox apps themselves are found only on third-party (non-Google Play) app stores.

HenBox apps appear to primarily target the Uyghurs – a Turkic ethnic group living mainly in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in North West China.

HenBox has ties to infrastructure used in targeted attacks, with a focus on politics in South East Asia. These attackers have used additional malware families in previous activity dating to at least 2015 that include PlugX, Zupdax, 9002, and Poison Ivy.

HexBox apps target devices made by Chinese consumer electronics manufacture, Xiaomi and those running MIUI, Xiaomi’s operating system based on Google Android. Furthermore, the malicious apps register their intent to process certain events broadcast on compromised devices in order to execute malicious code. This is common practice for many Android apps, however, HenBox sets itself up to trigger based on alerts from Xiaomi smart-home IoT devices, and once activated, proceeds in stealing information from a myriad of sources, including many mainstream chat, communication and social media apps. The stolen information includes personal and device information.

The main purpose of this follow-up blog is to provide additional information, and detailed analysis, about HenBox apps.

Delivery and Installation

During our investigation, we discovered one HenBox app previously hosted on the third-party Android app store, “uyghurapps[.]net”. This HenBox variant masqueraded as the legitimate VPN application, “DroidVPN”, and carried the app as an asset, embedded within itself. Once HenBox installs on a compromised device, it begins the installation process for the legitimate DroidVPN.

At the time of writing, we are unaware of any HenBox apps hosted on other third-party app stores; given the high volume of HenBox apps analyzed in our Wildfire sandbox, we can only speculate as to how other apps are delivered to victims; much of the Android malware seen in the wild tends to be delivered via third-party app stores, forums and file-sharing platforms, and of course by via ubiquitous phishing emails.

HenBox Decoys

Further analysis of the HenBox malware family is below, however, on the subject of masquerading apps, and installing embedded apps, it’s worth explaining how this decoy technique works.

The HenBox variant being described here relates to that listed in Table 1, below, which masquerades as DroidVPN; other apps were used with decoys, and are described in more detail in the previous blog.

| APK SHA256 | Size (bytes) | First Seen | App Package name |

App name |

| 0589bed1e3b3d6234c30061be3be1cc6685d786ab3a892a8d4dae8e2d7ed92f7 | 2,740,860 | May 2016 | com.android.henbox | DroidVPN |

Table 1 HenBox variant using decoy techniques

Once HenBox is installed, and launched by the victim, the app starts the installation process of the legitimate, embedded app by executing the following code.

|

1 2 3 |

Intent localIntent = new Intent("android.intent.action.VIEW"); localIntent.setDataAndType(Uri.fromFile(new File(str)), DaemonServer.a(new char[] { 56, 41, 41, 53, 48, 58, 56, 45, 48, 54, 55, 118, 47, 55, 61, 119, 56, 55, 61, 43, 54, 48, 61, 119, 41, 56, 58, 50, 56, 62, 60, 116, 56, 43, 58, 49, 48, 47, 60 })); startActivity(localIntent); |

Having created a new intent - android.intent.action.VIEW - at run-time, as opposed to declared statically in the app’s AndroidManifest.xml, the remaining code configures parameters relating to the embedded decoy app. The first argument to setDataAndType() contains said decoy app’s filename – res.apk – referenced as “str”.

Method a() of the DaemonServer class contains an XOR routine to decode the byte string argument using, in this case, a single-byte key 0x59. The following code snippet shows the decoded output used as the second argument to setDataAndType();

|

1 |

application/vnd.android.package-archive |

The decoded string shown above represents the Multipurpose Internet Mail Extensions (MIME) type associated with APK (Android app package) files.

Calling startActivity() with this intent configuration triggers Android to provide a handler – most likely the app package manager – that would prompt the victim to install the embedded application. Given, in this case, the victim most likely intended to install a VPN app, this secondary install for that app should come as no surprise, however, it’s likely the HenBox installation process would have also occurred and may have been more suspicious. Potential victims are likely lured into installing the apps through the use of app names, iconography, or other similar traits to those apps being sought; some HenBox apps purport to be system or back-up apps that may appear plausible to the victim.

Inside the Coop -HenBox Analysis

The following description is based on the HenBox app listed in Table 3 below. The reason for choosing this app for more detailed analysis, was the significant ties to infrastructure seen also having hosted Windows malware, such as PlugX.

| SHA256 | Package Name | App Name | First seen |

| a6c7351b09a733a1b3ff8a0901c5bde fdc3b566bfcedcdf5a338c3a97c9f249b |

com.android.henbox | 备份 (Backup) | Aug 29th 2017 |

Table 2 HenBox variant used in description

The majority of HenBox apps, including this one, used the following developer signature information to sign the APK file.

|

1 |

CN=henbox, OU=henbox, O=henbox, L=Guangzhou, ST=Guangdong, C=CN |

A smaller subset of HenBox apps used the “Android Debug” signature used typically when developers are testing their development. This shortcut is used to sign malicious apps, rather than the adversary creating their own signature, however there can be limitations as to where the app can be hosted and installed when using it. Recent HenBox apps have the common name (CN) changed to “h123enbox” or the entire signature as, simply, “C=cn”, where ‘C’ is the certificate attribute for Country.

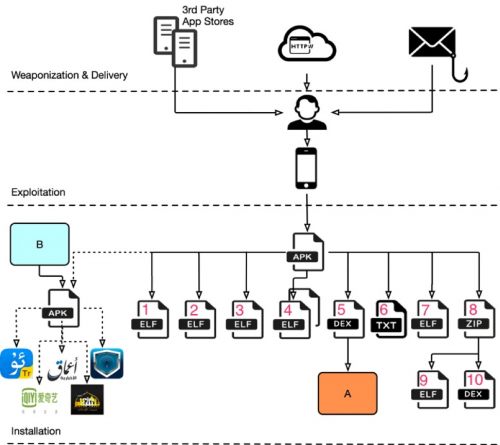

The following figures illustrate the structure of a typical HenBox app, how they are delivered, and the app behavior once installed.

Figure 1 HenBox app delivery and structure

In Figure 1 we included three methods for delivering HenBox commonly used by threat actors to deliver Android malware: websites, such as forums, phishing emails, and third-party app stores. It is likely HenBox is also delivered via the same methods. However, as previously mentioned, we do not have current visibility into delivery methods other than third-party app stores, for which we saw one instance.

To our knowledge, user interaction is required to install HenBox apps. Given the third-party app store we observed serving HenBox, and the decoy apps used, it’s clear the adversary relies heavily on social engineering techniques to compromise their victims.

Most HenBox apps seen to date contain a similar structure of files and components within the APK package. Optionally, as shown with the dotted line in Figure 2, and as described with the DroidVPN example earlier, HenBox apps may include an embedded APK file for use as a decoy. Another example of this is a HenBox sample that purports to be the popular online video platform iQiyi. That platform has over 500 million unique users, almost half of which are mobile viewers, providing yet another popular decoy app with which to social engineer potential victims.

Figure 1 above describes the structure of the HenBox app listed in Table 2 above. The numbered components from Figure 1 are listed in more detail in Table 3 below and described afterwards. Some of the components are RC4 encrypted using the downloaded-string key “a85fe5a8”; other components are XOR-encoded using various key values. Native libraries, in the form of Executable and Linkable Format (ELF) files, are common to HenBox samples and the Java Native Interface (JNI) allows the Android app components to communicate with and execute functions in these libraries.

| # | Filename | Obfuscation Compression |

Type | Purpose |

| 1 | ./assets/b.dat | RC4(Zlib) | ELF | Interacts with other components inside the a.zip archive. |

| 2 | ./lib/<cpu>/liblocsdk.so | N/A | ELF | Baidu library for device geo-location data. |

| 3 | ./lib/<cpu>/libloc4d.so | N/A | ELF | Handlies RC4 decryption, Zlib decompression and HTTP network communication. |

| 4 | ./assets/sux (and suy) | XOR (0x51) | ELF | Contains embedded SU (Super User) and other root-related capabilities to run privileged commands; Harvests messages and other private data from popular messaging and social media apps. |

| 5 | ./classes.dex | N/A | DEX | Main Dalvik file containing Java for HenBox |

| 6 | ./assets/setting.txt | XOR (0x88) | Data | Config file containing C2 and other information |

| 7 | ./assets/daemon | N/A | ELF | Starts services, monitors environment settings and system logs. |

| 8 | ./assets/a.zip | RC4(ZIP) | Archive | Zip archive containing two files |

| 9 | ./assets/a.zip/libkernel.so | N/A | ELF | Library handling various activities including loading a secondary Dalvik DEX file (lib.dat) |

| 10 | ./assets/a.zip/lib.dat | RC4(Zlib) | DEX | Dalvik file for parsing config file, monitoring out-going calls, intercepting SMS messages and more. |

Table 3 Contents and components of this HenBox variant

Chickens in flight

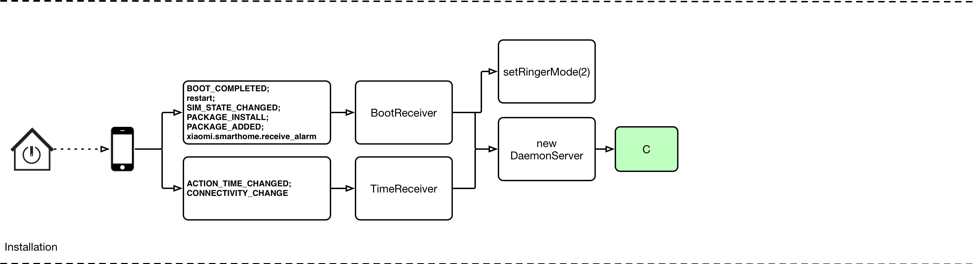

There are two methods to execute HenBox’s malicious code. The first method, as depicted by Figure 2 below, is automatic based on the operating system generating one of a handful of broadcasts that HenBox registered its intent to process during the app installation process. Examples include events like device reboots or when an app is newly installed. The list of all the intents registered statically via HenBox’s AndroidManifest.xml file are described in the appendix below; HenBox also registers further intents at run-time.

Figure 2 HenBox execution via Intents and External Triggers

Most of the intents listed in the appendix, and in Figure 2, are commonly found in malicious Android apps, and are the equivalent of setting registry run keys on Windows to autostart applications under certain conditions. One intent stands out and is much less common to see - com.xiaomi.smarthome.receive_alarm.

Xiaomi, a privately owned Chinese electronics and software company, is the 5th largest smart phone manufacturer in the world, manufacturing IoT devices for the home. Devices range from smart lights to smart rice cookers, and much more in-between. Devices are controlled using Xiaomi’s “MiHome” app, which has been downloaded between 1,000,000 and 5,000,000 times.

Given the nature of connected devices in smart homes, it’s highly likely many of these devices, and indeed the controller app itself, communicate with one another sending status notifications, alerts and so on. Such notifications, received by the MiHome app can also be processed by other apps, provided they register their intent to do so, such as HenBox. Essentially, this allows for external IoT devices to act as a trigger to execute the malicious HenBox app’s code.

Triggered intents result in execution of code that’s present in either the BootReceiver or TimeReceiver classes, both of which ultimately lead to a new instance of the DaemonServer service being created and started. This service is discussed in more detail later. In addition, BootReceiver changes the device ringer mode to a value of 2, which results in ringtones being audible, and setting vibrate mode on. This may have been done in an attempt to have nearby people interact with the (now noisy) device such that information stolen may be richer in content. For more information on these intents and their purpose, please see the appendix.

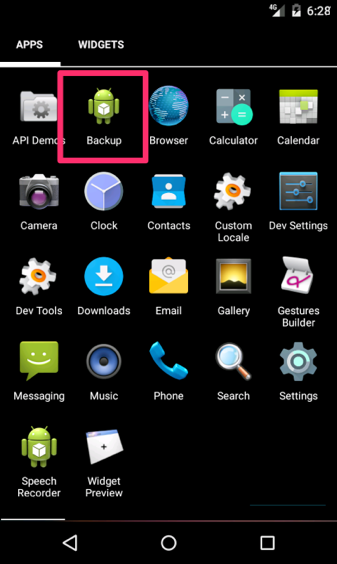

The alternative method for executing the HenBox code is for the user to launch the malicious app from the launcher view on their device, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3 HenBox app present in Launcher View on Android

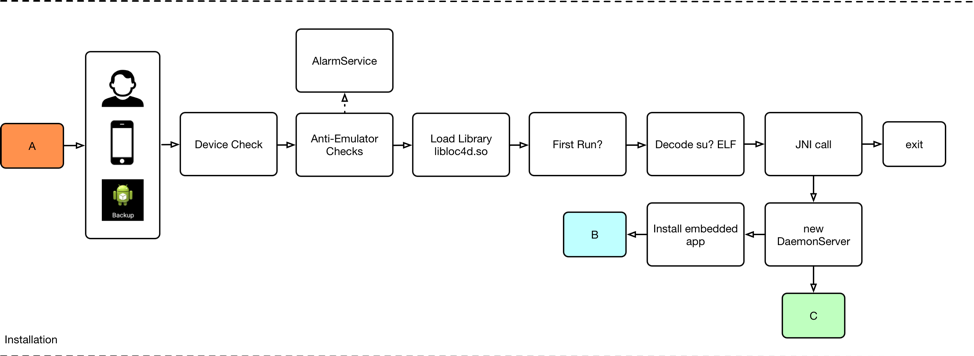

Upon manual launch, HenBox code executes and performs the steps highlighted in Figure 4 below.

Figure 4 HenBox execution via human interaction

Firstly, checks are made to determine whether the device manufacturer is Xiaomi, or the firmware is MIUI (Xiaomi’s fork of Android). The intention here seems to be one of targeting Xiaomi and exiting prematurely if the checks fail, however poorly written code results in execution in more environments than the adversary perhaps wanted. Further checks try to ascertain whether HenBox is running on an emulator, perhaps being cautious around potential researcher environments. Interestingly, the code for these additional checks are concealed inside a class called AlarmService, which is appears to be code from online tutorials for Android developers, perhaps to hide the adversary’s code from plain sight. Assuming these checks pass, HenBox continues to execute by next loading the ELF library libloc4d.so; its functionality is discussed later in this blog.

Using Android’s shared preferences feature to persist XML key-value pair data, HenBox checks whether this execution is its first. If it is, and if the app’s path does not contain “/system/app” (i.e. HenBox is not running as a system app, which provides elevated privileges), one of two embedded “su?” ELF libraries are XOR-decoded. A JNI call is then issued to libloc4d.so passing three strings – the app’s package name, the package name including the current class, which is “MainActivity”, and the path to the HenBox app. This JNI call leads to the execution of the “su?” (henceforth sux) binary, which is also discussed in more detail later.

The two files – “suy” and “sux” – are essentially the same; “sux” is used if the Android version on the victim’s device is 4.1 (aka “Jelly Bean”) or newer; “suy” will be used for older versions.

Finally, an instance of the DaemonServer service starts and, if a decoy app is embedded inside HenBox, as per the DroidVPN example, the installation process for it also starts.

DaemonServer Class

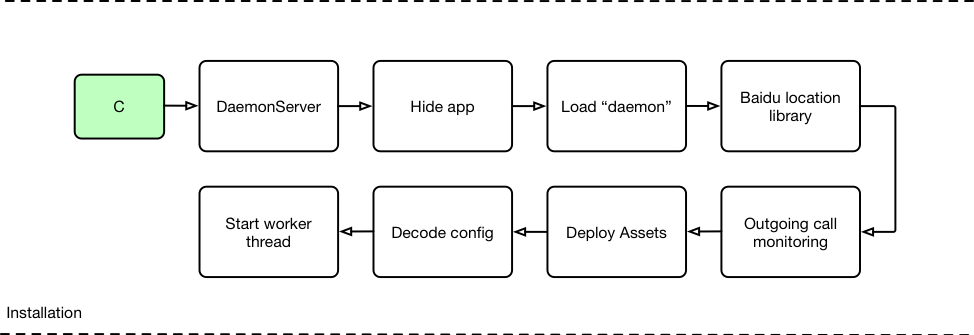

Figure 5 below illustrates the typical behavior of the DaemonServer service, starting with hiding the HenBox app from the launcher view and the app drawer/tray. This behavior is common amongst Android malware and, while the app remains installed with its services running, it is harder to discover by the victim. The non-obfuscated ELF file “daemon” is loaded next; the program gathers environmental information about the device by accessing system and radio log files, and by querying running processes.

Figure 5 HenBox's DaemonServer Service code execution flow

A Baidu library is used to for gathering device geo-location information; another run-time intent is registered to intercept outgoing phone calls, allowing HenBox to check the number dialed for prefixes matching “+86” – the country code for the People’s Republic of China. Interestingly, instead of using Baidu’s coordinate system, HenBox specifies the GCJ-02 alternative provided by the Chinese State Bureau of Surveying and Mapping. According to public sources, this system adds apparently random offsets to both the latitude and longitude, with the alleged goal of improving national security.

Further assets are then deployed and decoded, if necessary, including a.zip and setting.txt. Code is present in this variant to also deploy assets named “plugin” and “AppVoice”, however, they are not present in this sample, a likely indication of evolving development and use of multiple components, depending the adversary’s needs at a given time.

HenBox’s config file, setting.txt, is decoded using XOR with a single-byte key, 0x88; filenames and XOR keys differ occasionally between variants. Once de-obfuscated, the config file’s contents resembles something like the following text:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 |

a1=wd.w3.ezua[.]com a2=80 a3=crash_report@21cn[.]com a4=smtp.21cn[.]com a5=crash_report a6=lxy.cn@163[.]com a7= a8=0914D1D428914B09A5372866B39524B9 a9= b1=0 b2=0 b3=1 b4=http://www3.mefound[.]com/aa.txt |

Interestingly, open source research indicates the email address in the above HenBox config file belongs to a scholar of Cyber Security at the University of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing, China. They are listed as an author on the paper “Recognition of Information Leakage of Computer via Conducted Emanations on the Power Line.” Why the email appears in the configuration file of HenBox malware is not known at the time of writing.

Currently, it’s not known to us exactly how all these parameters are used, however some of the domains (or IP addresses in other variants) are used as the C2 for the threat actors.

Finally, a worker thread is then created that sets various components running in the background. One of the key components used is the ELF file named “b.dat”, which in turn interacts with “a.zip”. The archive file a.zip contains two further files: libkernel.so (another ELF file) and lib.dat, which is actually a Dalvik DEX file containing further Java code for the app’s behavior, beyond the default classes.dex file. Some of the key data-harvesting behavior of HenBox stem for these files – b.dat and the contents of a.zip – all four of which are RC4-encrypted, forming the most heavily obfuscated components within HenBox.

Once unpacked and available for use, the new DEX file is executed from within the DaemonServer class of the main HenBox app. A DexClassLoader object is created and a loadClass method is called for a class "com/common/ICommonFun" contained within the once deeply-nested, and obfuscated secondary DEX file. From the newly-loaded class, a method is called to invoke further HenBox capabilities, including enumerating all running applications and killing those that have the permission to receive SMS messages, before registering its own run-time Intent to do so, and thus intercept the victim’s messages.

The method continues next by loading the libkernel.so library file, also unpacked from the a.zip archive. This ELF file has numerous capabilities, many of which stem from using a built-in version of BusyBox – a package containing various stripped-down Unix tools useful for administering such systems. This executable interacts with the aforementioned sux executable and, amongst other things, temporarily disables the noise made by the device when photos are taken. This is achieved by moving the audio file “/system/media/audio/ui/camera_click.ogg” elsewhere, and back again once the picture-taking is complete.

Dynamic C2s

At the time of writing, three HenBox variants, all seen in early April 2017, gathered their C2 addresses dynamically. The three are listed in Table 3, below.

| SHA-256 | Package Name | App Name | First Seen |

| 184e5cbebef4ee591351cfaa1130d5741 9f70eb95c6387cb8ec837bd2beb14d6 |

com.android.henbox | 备份 (Backup) | April 2nd 2017 |

| efa3cd45e576ef8ab22d40fc9814456d0 6a6eeeaeada829c16122a39cb101dbf |

com.android.henbox | 备份 (Backup) | April 2nd 2017 |

| 9d85be32b54398a14abe988d98386a3 8ce2d35fff91caf1be367f7e4b510b054 |

com.android.henbox | 备份 (Backup) | April 1st 2017 |

Table 4 HenBox variants using dynamic C2s

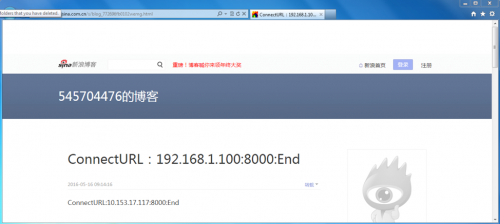

As previously mentioned, HenBox config files contain the C2 information for the malware. In the case of the three variants listed in Table 3, the C2 address was http://blog.sina.com[.]cn/s/blog_772696fb0102wemg.html. The content of the site, at the time of writing, is shown in Figure 6 below.

Figure 6 Example website hosting the HenBox C2 information

The blog contains structured text strings beginning with “ConnectURL” that, when parsed, provide the IP address and port number for HenBox to use as its C2.

Conclusion

Typically masquerading as legitimate Android system apps, and sometimes embedding legitimate apps within them, the primary goal of the malicious HenBox apps appears to be to spy on those who install them. Using similar traits, such as copycat iconography and app or package names, victims are likely socially engineered into installing the malicious apps, especially when available on so-called third-party (i.e. non-Google Play) app stores which often have fewer security and vetting procedures for the apps they host. It’s possible, as with other Android malware, that some apps may also be available on forums, file-sharing sites or even sent to victims as email attachments, and we were only able to determine the delivery mechanism for a handful of the apps we have been able to find.

The hosting locations seen for some HenBox variants, together with the nature of some embedded apps including: those targeted at extremist groups, those who use VPN or other privacy-enabling apps and those who speak the Uyghur language, highlights the victim profile the threat actors were seeking to attack. The targets and capabilities of HenBox, in addition to the ties to previous activity using four different Windows malware families with political-themed lures against several different South East Asian countries, indicates this activity likely represents an at least three year old espionage campaign.

Palo Alto Networks customers are protected by:

Autofocus customers can investigate this activity using the following tag. To date we believe HenBox is not a shared tool, however, the remainder of malware used by these attackers is shared amongst multiple groups:

Android Hygiene

Update: Keep installed apps updated. Much like patching Operating System and application files on PCs, Android and apps developed for the platform also receive security updates from Google and app developers to remove vulnerabilities and improve features, including security.

Review: App permissions to see what the app is potentially capable of. This can be quite technical but many permissions are named intuitively describing if they intend to access contacts, messages or sensors, such as the device microphone or camera. If you the permission seem over the top compared to the described functionality, then don’t install. Also read the app and developer reviews to evaluate their trustworthiness.

Avoid: 3rd party app stores that may host pirated versions of paid apps from the Google Play app store, often such apps include unwanted extra features that can access your sensitive data or perform malicious behaviors. Also avoid rooting devices, if possible, as apps could misuse this power.

Appendix

The following analysis is based on the HenBox Android APK file listed in Table 5 below.

| SHA256 | Package Name | App Name | First seen |

| a6c7351b09a733a1b3ff8a0901c5bde fdc3b566bfcedcdf5a338c3a97c9f249b |

com.android.henbox | 备份 (Backup) | Aug 29th 2017 |

Table 5 HenBox app detailed in the analysis

The permissions declared statically in the AndroidManifest.XML file are pretty aggressive, and in line with what you would expect from this type of espionage Android malware. Table 6 below lists and describes the Android permissions declared for this variant of HenBox.

| Category | Permission | Description |

| System | KILL_BACKGROUND_PROCESSES | The ability to kill processes associated to given packages may allow the app to stop security apps, or those that may be running, which it is attempting to imitate or install. |

| System | WAKE_LOCK | Allows for the CPU to be kept awake, and screen on, for background tasks to continue. |

| System | WRITE_SETTINGS** | Ability to modify system settings |

| System | RECEIVE_BOOT_COMPLETED | Can receive the broadcast message when system finishes booting. |

| System | READ_LOGS | Allows for reading the low-level system log files. |

| System | GET_TASKS | Retrieve the list of running tasks from all apps. |

| Storage | MOUNT_UNMOUNT_FILESYSTEMS | (un)mount file systems for removable storage access. |

| Storage | WRITE_EXTERNAL_STORAGE | Write to external storage. |

| Sensors | CAMERA | Access the device camera(s) |

| Sensors | RECORD_AUDIO | Record audio through device microphone |

| Network | INTERNET | Ability to open network sockets |

| Network | ACCESS_NETWORK_STATE | Access information about phone networks |

| Network | ACCESS_WIFI_STATE | Access information about WiFi networks |

| Network | CHANGE_WIFI_STATE | Change Wi-Fi connectivity state |

| Network | CHANGE_NETWORK_STATE** | Change network connectivity state |

| Messages | READ_SMS | Read SMS messages |

| Messages | RECEIVE_SMS | Receive SMS messages |

| Messages | SEND_SMS | Send SMS messages |

| Messages | WRITE_SMS** | Write SMS messages |

| Location | ACCESS_COARSE_LOCATION | Access approximate location |

| Location | ACCESS_FINE_LOCATION | Access precise location |

| Contacts | READ_CONTACTS | Read user’s contacts data |

| Contacts | WRITE_CONTACTS | Write to the user’s contacts data |

| Calls | READ_PHONE_STATE | Read-only access to device phone number, current cellular network information and the status of any ongoing calls. |

| Calls | READ_CALL_LOG | Read the call log of previous outgoing, incoming and missed calls. |

| Calls | READ_PHONE_STATE (duplicate) | (see above) |

| Calls | PROCESS_OUTGOING_CALLS | Ability to see the number being dialed during an outgoing call with the option to redirect the call to a different number or abort the call altogether |

| Calls | CALL_PHONE | Initiate a phone call without going through the Dialer user interface for the user to confirm the call |

| Calls | WRITE_CALL_LOG | Write to the user's call log data |

| Calendar | READ_CALENDAR | Read the user's calendar data |

| Browser | browser.permission. READ_HISTORY_BOOKMARKS** |

Access browsing history from web browser(s) |

Table 6 Typical permissions requested by HenBox

**Some permissions are deprecated in recent Android versions, or now require more stringent permission requests including user-interaction for secondary permission acceptance; in some cases, 3rd party apps may no longer be allowed to use some of the listed permissions. The ability to write SMS messages, for example, was overhauled in version 4.4 (aka KitKat) some 4 years ago.

Some variants have slightly differing permissions; noteworthy that some recent variants of HenBox have included Bluetooth related permissions, as detailed in Table 7 below.

| Category | Permission | Description |

| Network | BLUETOOTH | Allows applications to connect to paired bluetooth devices |

| Network | BLUETOOTH_ADMIN | Allows applications to discover and pair bluetooth devices. |

Table 7 Additional permissions in more recent HenBox variants

Once the user installs the app, two services are registered, as shown in Figure 7 below – showing an extract from this app’s AndroidManifest.xml file.

![]()

Figure 7 AndroidManifest.xml service declarations

Both services have been discussed already but to recap, DaemonServer is responsible for hiding the malicious app, enabling location tracking and gathering phone numbers called from the device, with specific interest of Chinese numbers; further components are also unpacked and launched when this class is instantiated and run.

AlarmService contains an approximate copy of Google’s Android API demo code for creating alarm and timer apps. Extra classes and methods have been added providing functionality to HenBox, including anti-debug and anti-analysis code capable of detecting if the app is running within emulator, and possibly research analysis, environments.

Manifest-declared priority values of 1000 are set for both services, as shown in Figure 7, albeit erroneously. Setting high, or in this case maximum, values in the priority attribute is a trick typically used when declaring intents and receivers for system broadcasts to ensure certain apps (often malicious) are executed ahead of intended apps that would handle such events. There is no such priority concept for services; the operating system alone controls service CPU time, according to how busy the device is and how much resource remains.

The attribute “exported”, shown in Figure 7, relates to whether or not components of other applications can invoke the service, or interact with it — "true" if they can; "false" if not. This immediately makes DaemonServer a little more interesting.

Android receivers com.android.henbox.BootReceiver and com.android.henbox.TimeReceiver are also declared in the AndroidManifest.xml to receive broadcast messages under certain conditions. BootReceiver, as per the services listed in Figure 7 above, has its priority attribute (correctly) set to 1000, allowing certain intent-filters to trigger and run the malicious receiver above the receivers and matching intents from other apps.

The intent filters listed in the AndroidManifest.xml are briefly described in the Table 8 below, together with the receivers they refer to.

| Receiver | Intent Name | Description |

| BootReceiver | android.intent.action.BOOT_COMPLETED | System notification that the device has finished booting. |

| android.intent.action.restart | A legacy intent used to indicate a system restart. | |

| android.intent.action.SIM_STATE_CHANGED | System notification that the SIM card has changed or been removed. | |

| android.intent.action.PACKAGE_INSTALL | System notification that the download and eventual installation of an app package is happening (this is deprecated) | |

| android.intent.action.PACKAGE_ADDED | System notification that a new app package has been installed on the device, including the name of said package. | |

| com.xiaomi.smarthome.receive_alarm | Received notifications from Xiaomi’s smart home IoT devices. | |

| TimeReceiver | android.intent.action.ACTION_TIME_CHANGED | System notification that the time was set. |

| android.intent.action.CONNECTIVITY_CHANGE | System notification that a change in network connectivity has occurred, either lost or established. Since Android version 7 (Nougat) this information is gathered using other means, perhaps inferring the devices used by potential victim run older versions of Android. | |

Table 8 HenBox intents declared statically in AndroidManifest.xml

Most of the intents listed are commonly seen in malicious, information-stealing Android apps that wish to hook certain common events, such as system reboots, network changes, new apps installed and so forth, acting as a trigger to their code.

As mentioned earlier, HenBox registers a much less common and more interesting intent filter – com.xiaomi.smarthome.receive_alarm. This relates to Xiaomi’s smart home IoT devices, and their MiHome controller app for smartphones. Broadcasts or notifications from such Xiaomi’s devices, which would usually be processed by the MiHome app, could now also be processed by HenBox, acting as a trigger to launch its malicious behavior.

Whichever Intent triggers HenBox will execute code declared in BootReceiver or TimeReceiver; both receivers’ code resembles the snippet below, which starts a new instance of the service DaemonServer and increment an integer by 1.

|

1 2 |

DaemonServer.d += 1; paramContext.startService(new Intent(paramContext, DaemonServer.class)); |

BootReceiver also executes the following line of code, resulting in the device’s ringer mode being set to audible and vibrate mode on.

|

1 |

((AudioManager)paramContext.getSystemService("audio")).setRingerMode(2); |

The purpose for this additional behavior in BootReceiver is unknown but given the requested permissions, the capability to gather information from device sensors, such as the microphone and cameras, it’s feasible the intention of changing the ringer settings is to encourage interaction with the device by anyone nearby, perhaps leading to richer content of the data being exfiltrated.

Aside from using Intents and Receivers to launch HenBox, as mentioned above, there is an alternative – launching the app manually from the launcher view on Android, as shown in Figure 8 below. Doing so results in code in the MainActivity class being executed, which is equivalent to a Windows Portable Executable (PE) file’s entry point.

Figure 8 Android app launcher view and the HenBox app

Specifically, the onCreate() method in the MainActivity class is executed. This code performs some initial checks of the device manufacturer and Operating System before continuing. The actors seemed to be interested only in Xiaomi devices, or Xiaomi’s fork of Android called MIUI (“Me You I”) running on any device. The code performing these checks is buggy and results in execution in more environments then perhaps anticipated.

Continuing with the device checks, HenBox performs various well-documented anti-emulator checks, such as querying the device phone number, device IDs, IMSI, various QEMU-related environment settings, hardware configurations and other notable strings to compare against known constants that would infer an emulator device, which are commonly used for app analysis. Finally, they check for tainted Operating Systems, such as the presence of TaintDroid code used for tracking app behavior.

Android’s shared preferences feature is used to persist information beyond the lifetime of the app execution, and to retrieve said information, should it exist. HenBox uses this feature to symbolize if the malware has already run. The strings used to denote this are XOR-encoded with single-byte key, 0x59; a helper method in the DaemonServer class is used for decoding. The strings are listed in Table 9 below.

| # | Encoded | Decoded |

| 1 | 41 43 60 63 60 43 60 55 58 60 | Preference |

| 2 | 31 48 43 42 45 11 44 55 | FirstRun |

| 3 | 0 28 10 | YES |

| 4 | 118 42 32 42 45 60 52 118 56 41 41 | /system/app |

Table 9 Example HenBox XOR encoded strings

HenBox attempts to hide itself from the app launcher view by running the following code, passing the parameters COMPONENT_ENABLED_STATE_DISABLED (2) and DONT_KILL_APP (1) to the setComponentEnabledSetting() method.

|

1 |

getPackageManager().setComponentEnabledSetting(new ComponentName(this, MainActivity.class.getName()), 2, 1); |

DaemonServer Service

To recap, the DaemonServer Service is launched either through the two receivers’ intent filters being triggered by certain events occurring on the device, or through launching the app manually. Either way, the registered service’s entry-point method, onCreate(), is executed.

Location tracking for the device is enabled using the com.baidu.location.service_v2.9 libraries carried within the HenBox APK file. However, instead of using Baidu’s coordinate system, HenBox specifies the GCJ-02 alternative provided by the Chinese State Bureau of Surveying and Mapping. According to public sources, this system adds apparently random offsets to both the latitude and longitude, with the alleged goal of improving national security.

DaemonServer continues by setting up a PhoneStateListener object instance, customized to handle cases of phone numbers starting with “+86” (country dialing code for China), and listens for changes to the device call state. A run-time, high-priority intent filter is setup for android.intent.action.NEW_OUTGOING_CALL, so as to inform HenBox when a phone call is made. The associated receiver – BroadcastReceiver – retrieves the phone number being dialed using the getStringExtra("android.intent.extra.PHONE_NUMBER") method call.

IOCs

For a full list of SHA256 hashes, their first encountered timestamp, and details of Android package and app names relating to over 200 apps, please refer to the following file on GitHub.

Get updates from

Palo Alto

Networks!

Sign up to receive the latest news, cyber threat intelligence and research from us

By submitting this form, you agree to our Terms of Use and acknowledge our Privacy Statement.