Continuing our theme of using IDAPython to make your life as a reverse engineer easier, I’m going to tackle a very common issue: shellcode and malware that uses a hashing algorithm to obfuscate loaded functions and libraries. This technique is widely used and analysts come across it often. Using IDAPython, we will take this challenging problem and defeat it quite easily.

Background

Reverse engineers most often encounter obfuscated function names in shellcode. The process is quite simple overall. The code will initially load the kernel32.dll library at runtime. Then, it continues to use this loaded image to identify and store the LoadLibraryA function, which is used to load additional libraries and functions. This particular technique employs a hashing algorithm that is used to identify a function. The hashing algorithm is commonly CRC32, however, other variations, such as ROR13, are common as well.

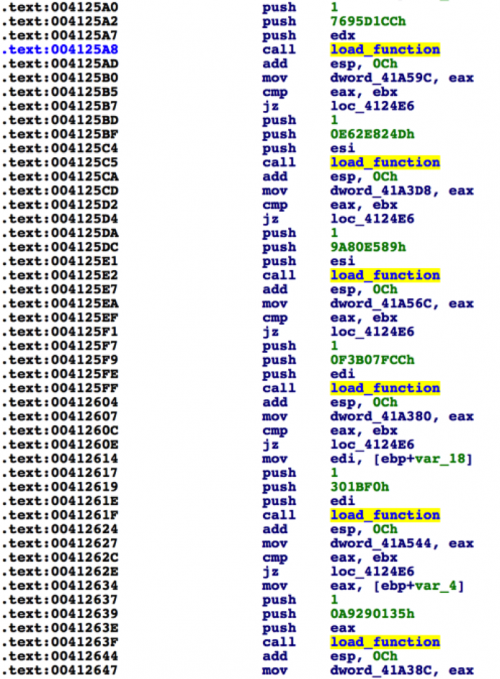

While reverse engineering a piece of malware, I ran into the following technique:

Figure 1 Malware loading functions dynamically using CRC32 hash

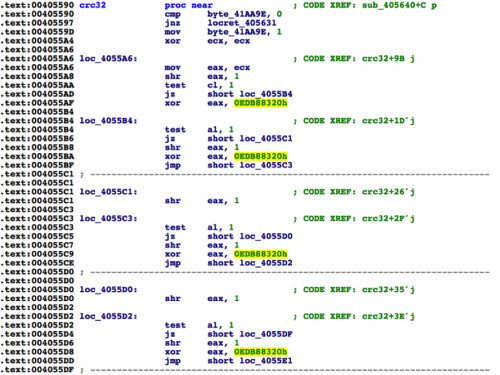

In the above example, we were able to quickly identify the constant of 0xEDB88320, which is used by the CRC32 algorithm.

Figure 2 CRC32 algorithm identified

Now that the algorithm and function have been identified, we can look at the number of cross-references to determine how many times this function is called. In total, this function is called 190 times in this particular sample. Clearly, decoding all of these hashes and renaming them by hand within our IDA Pro file is not something we wish to perform. As such, we can use IDAPython to make our lives easier.

Scripting in IDAPython

The first step actually does not use IDAPython whatsoever, but it does use Python. In order to identify what hashes equate to what functions, we need to generate a list of the most common function hashes on a Microsoft Windows operating system. To do this, we can simply grab a list of common libraries used by the Windows OS, and iterate over their function names.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 |

def get_functions(dll_path): pe = pefile.PE(dll_path) if ((not hasattr(pe, 'DIRECTORY_ENTRY_EXPORT')) or (pe.DIRECTORY_ENTRY_EXPORT is None)): print "[*] No exports for %s" % dll_path return [] else: expname = [] for exp in pe.DIRECTORY_ENTRY_EXPORT.symbols: if exp.name: expname.append(exp.name) return expname |

We can then take this list of function names and perform the CRC32 hashing algorithm against it.

|

1 2 |

def calc_crc32(string): return int(binascii.crc32(string) & 0xFFFFFFFF) |

Finally, we write the results to a JSON-formatted file, which I’ve named ‘output.json’. This JSON data file contains a large dictionary, using the following format:

|

1 |

HASH => NAME |

A full copy of this script can be found here.

Once this file has been generated, we can go back to IDA, where the remainder of our scripting will take place. The first step of our script will be to read the JSON data from the previously created ‘output.json’. Unfortunately, JSON objects to not support using integers as the key value, so after this data is loaded, we modify the keys to represent integers instead of strings.

|

1 2 |

for k,v in json_data.iteritems(): json_data[int(k)] = json_data.pop(k) |

After this data has been properly loaded, we’re going to create a new enumeration that will store the hash-to-function-name mapping. (For more information about enumerations and how they work, I encourage you to read this tutorial.)

Using enumerations, we’re able to map an integer value, such as a CRC32 hash, to a string representation, such as a function name. In order to create a new enumeration in IDA, we make use of the AddEnum() function. To make the script more versatile, we first check to see if the enumeration already exists, using the GetEnum() function.

|

1 2 3 |

enumeration = GetEnum("crc32_functions") if enumeration == 0xFFFFFFFF: enumeration = AddEnum(0, "crc32_functions", idaapi.hexflag()) |

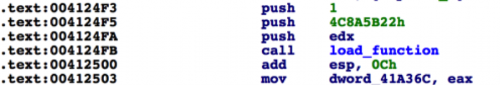

This enumeration will be modified later on. The next step will be to determine what cross-references our function responsible for converting hashing to function has. This should look familiar to those that have read part 1. When looking at the structure of how functions are passed to the function, we see that the CRC32 hash is provided as the second argument.

Figure 3 Arguments being passed to load_function

As such, we’re going to iterate through the previous instructions leading up to the function call, looking for the second instance of a push instruction. Once discovered, we check the CRC32 hash against our previously loaded JSON data from output.json to ensure this value has a function name associated with it.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 |

for x in XrefsTo(load_function_address, flags=0): current_address = x.frm addr_minus_20 = current_address-20 push_count = 0 while current_address >= addr_minus_20: current_address = PrevHead(current_address) if GetMnem(current_address) == "push": push_count += 1 data = GetOperandValue(current_address, 0) if push_count == 2: if data in json_data: name = json_data[data] |

At this point, we add this CRC32 hash and function name to our previously created enumeration, using the AddConstEx() function.

|

1 |

AddConstEx(enumeration, str(name), int(data), -1) |

Once this data has been added to the enumeration, we can convert our CRC32 hash to its enumeration name. The following two functions can be used to acquire the first instance of a number to its enumeration, as well as convert data at a certain address to this enumeration.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 |

def get_enum(constant): all_enums = GetEnumQty() for i in range(0, all_enums): enum_id = GetnEnum(i) enum_constant = GetFirstConst(enum_id, -1) name = GetConstName(GetConstEx(enum_id, enum_constant, 0, -1)) if int(enum_constant) == constant: return [name, enum_id] while True: enum_constant = GetNextConst(enum_id, enum_constant, -1) name = GetConstName(GetConstEx(enum_id, enum_constant, 0, -1)) if enum_constant == 0xFFFFFFFF: break if int(enum_constant) == constant: return [name, enum_id] return None def convert_offset_to_enum(addr): constant = GetOperandValue(addr, 0) enum_data = get_enum(constant) if enum_data: name, enum_id = enum_data OpEnumEx(addr, 0, enum_id, 0) return True else: return False |

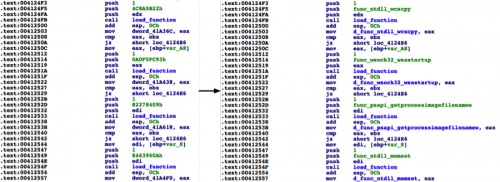

After this enumeration conversion has taken place, we’re going to take a look at renaming the DWORD that holds the address of the discovered function after it is loaded.

Figure 4 Storing function address to DWORD after it is loaded

To do this, we will iterate not before the function, but after, looking for an instruction that is moving eax to a DWORD. When this is discovered, we’ll rename this DWORD to the correct function name. To avoid naming conflicts, we will prepend ‘d_’ to the name.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

address = current_address while address <= address_plus_30: address = NextHead(address) if GetMnem(address) == "mov": if 'dword' in GetOpnd(address, 0) and 'eax' in GetOpnd(address, 1): operand_value = GetOperandValue(address, 0) MakeName(operand_value, str("d_"+name)) |

Putting this all together, we’re able to update the previous unreadable disassembly to something much more readable.

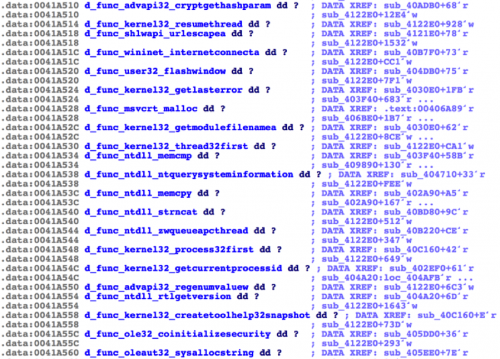

Figure 5 Changes after running script

Now, when we look at the list of DWORDs being used to store this information, we get a list of actual function names. This data can then be used to perform additional static analysis against the malware in question.

Figure 6 DWORD naming after script runs

The full IDAPython script can be found here.

Conclusion

We were once again able to take a fairly difficult task of being provided with 190 CRC32 hash representations of function names and extracting meaningful data using IDAPython. Enumerations can be a powerful mechanism when faced with such a problem. Creating and modifying enumerations, and assigning enumerations to variables can be easily performed using IDAPython, saving us valuable time. Additionally, these enumerations can be exported and imported into other IDA projects in the event an analyst finds the same challenge while reverse engineering another sample.

Addendum 12/31/2015: As pointed out to me by Alex Hanel on Twitter, in the event you rename the function to its actual function name, IDA Pro will automatically perform parameter propagation. This adds an additional level of information to the analyst, making static analysis easier. A simple modification to the script mentioned earlier in this blog post will allow the analyst to perform this action. In the event the name already exists, simply add a '_' or '_1' to it in order to avoid conflicts.

Get updates from

Palo Alto

Networks!

Sign up to receive the latest news, cyber threat intelligence and research from us

By submitting this form, you agree to our Terms of Use and acknowledge our Privacy Statement.