Unit 42 recently published a blog on a newly identified Trojan called Bookworm, which discussed the architecture and capabilities of the malware and alluded to Thailand being the focus of the threat actors’ campaigns.

In this blog, we will discuss the current attack campaign along with the associated threat infrastructure and the actor’s tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs). The following list provides a summary of the threat actors TTPs, which we will cover in this blog:

- Actively attacking targets in Thailand, specifically government entities.

- Uses Bookworm Trojan as the payload in attacks.

- Has access to compromised servers that they use to download Bookworm.

- Known to use spear-phishing as the attack vector to compromise targets, but have access to compromised web servers that could facilitate strategic web compromise (SWC) as an attack vector in the future.

- Uses standalone Flash Player to play slideshows that contain pictures of current events in Thailand as decoy documents, but also use the legitimate Flash Player installation application as a decoy in some instances.

- Uses date codes to track campaigns or Trojan version. If date codes are indeed used for campaign identifiers, then the dates precede attacks or current event seen in decoys by 6 to 18 days, which provides a glimpse into the development and operational tempo of this group.

- Use of large command and control (C2) infrastructure, which heavily favors dynamic DNS domains for C2 servers.

- Deployed Poison Ivy, PlugX, FFRAT and Scieron malware families.

Bookworm Attack Campaign

Threat actors have delivered Bookworm as a payload in attacks on targets in Thailand. Readers who are interested in this campaign should start with our first blog that lays out the overall functionality of the malware and introduces its many components.

Unit 42 does not have detailed targeting information for all known Bookworm samples, but we are aware of attempted attacks on at least two branches of government in Thailand. We speculate that other attacks delivering Bookworm were also targeting organizations in Thailand based on the contents of the associated decoys documents, as well as several of the dynamic DNS domain names used to host C2 servers that contain the words “Thai” or “Thailand”. Analysis of compromised systems seen communicating with Bookworm C2 servers also confirms our speculation on targeting with a majority of systems existing within Thailand.

Static Date Codes and Decoys

As mentioned in our previous blog on Bookworm, the Trojan sends a static date string to the C2 server that we referred to as a campaign code. We believed that the actors would use this date code to track their attack campaigns; however, after continued analysis of the malware, we think these static dates could also be a build identifier for the Trojan. It is difficult to determine the exact purpose of these static date codes with our current data set, but we will cover both possibilities in the next sections. While we currently favor the theory that these dates act as campaign codes, we extracted the following unique date codes from all known Bookworm that suggests the threat actors began their campaign in June or July 2015:

- 20150626

- 20150716

- 20150801

- 20150818

- 20150905

- 20150920

Trojan Build Dates

Threat actors may use the date string hardcoded into each Bookworm sample as a build identifier. A Trojan sending a build identifier to its C2 server is quite common, as it notifies the threat actors of the specific version of the Trojan in which they are interacting. As mentioned in our previous blog, Bookworm is fairly complex based on its modular framework, which suggests that the threat actors would need to know the exact version of the Trojan they are communicating with in order to install appropriate supplemental modules.

While a plausible premise, our data set does not fully support the hardcoded dates in Bookworm samples as a build identifier. To attempt to confirm the dates acting as a build ID, we extracted all of the modules for each Bookworm sample. We then compared the modules of each Bookworm sample that had the same date values. Most of the modules were identical amongst Bookworm samples using the same date string, but several samples had differing modules yet the same date string. For instance, Table 1 shows two sets of Bookworm samples with the “20150716” and “20150818” date codes that have completely different Leader.dll modules.

| Date Code | Leader.dll Module | Compile Date |

| 20150716 | e602a12e8173ca17ba4a0c6c12a094c1 | 2015-07-18 |

| 20150716 | 4537257cb69a467a63c5a561825571f9 | 2015-07-23 |

| 20150818 | e6cb32805bc5d758a5ea1dcd3c05beb8 | 2015-08-24 |

| 20150818 | 7065c709dd9dc7072dd5a5e2904c2d78 | 2015-08-31 |

Table 1 Two sets of Bookworm samples that share a sttic date cod but have different Leader modules

If the Bookworm developers used the date code as a build identifier, it would suggest that a new date code would have been added to samples using the new Leader module. Due to these changes without a new date string, we believe the date codes are used for campaign tracking rather than a Bookworm build identifier. Unit 42 will continue to compare the date codes to the Bookworm modules in future samples and will modify our assessment if indications suggest the date string is indeed a build identifier.

Campaign Codes

We believe that Bookworm samples use the static date string as campaign codes, which we used to determine the approximate date of each attack that we did not have detailed targeting information. We also compared these campaign codes to the date the attacks occurred or the date of the event seen in decoy documents to get a sense of the threat group’s internal operations.

A number of the Bookworm samples include a decoy that is opened during installation of the malware in an attempt to disguise the compromise. The threat actors have used two types of decoys thus far: a legitimate Flash Player installation application and a standalone Flash application to display a photo slideshow. The use of a Flash Player installer, seen in Figure 1, suggests that the threat actors are using social engineering to instruct the victim to update or install the Flash Player application. The Bookworm campaign code “20150818” was used in all samples associated with these legitimate Flash Player installers.

Unit 42 has witnessed six decoy slideshows used in a Bookworm campaign targeting Thailand. All six of these decoy slideshows contain pictures that in some manner relate to Thailand. One known decoy includes an animation of what appears to be children in Thailand going to temple (Figure 2), which is associated with a spear-phishing attack on a branch of the Thailand government that occurred on July 27, 2015. The decoy’s filename is “wankaophansa.exe” that suggests the animation is regarding Wan Kao Phansa, which is a term for first day of the three month long rainy season. Wan Kao Phansa is a national holiday in Thailand, which in 2015 started on July 31. The attack occurred four days before the actual holiday and had a campaign code of “20150716”, which is eleven days before the attack took place.

We do not have detailed targeting information on the attacks that delivered the remaining five decoy slideshows. To determine the approximate date of these attacks, we compared the Bookworm campaign code associated with each decoy slideshow and found that they coincide with the timeline of events seen in the photos in the decoy slideshows.

Three of the decoys analyzed are related to the August 17, 2015 bombing near the Erawan Shrine in Bangkok, Thailand, as seen in Figures 3, 4 and 5. The campaign code “20150801” is associated with the decoy slideshow showing the graphic Erawan Shrine bombing (Figure 3), which is 16 days before to the actual event took place.

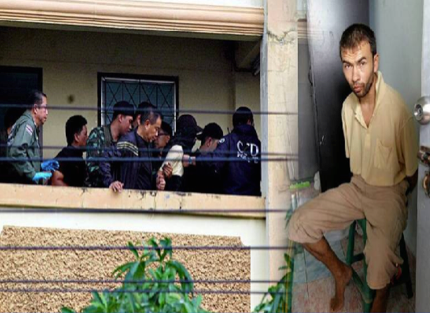

The second bombing-related decoy, seen in Figure 4 contained pictures of the arrest of a bombing suspect named Adem Karadag. This arrest was made on August 29, 2015, which is 11 days after the campaign code “20150818” that was associated with the decoy slideshow.

The third and final bombing-related decoy slideshow contains pictures of Adem Karadag re-enacting his role in the bombing for police (Figure 5). This re-enactment is a standard procedure for Thai police, which in this particular case took place on September 26, 2015. The campaign code “20150920” is associated with this decoy, which is six days before the actual event took place.

Another decoy slideshow associated with the Bookworm attack campaign contains photos of an event called Bike for Dad 2015. Bike for Dad is a cycling event that will be held on December 11, 2015 to commemorate the King of Thailand Bhumibol Adulyadej’s 88th birthday. Many high profile figures in Thailand are promoting this event, such as the Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha who is seen in many of images in the decoy slideshow (Figure 6).

The campaign code “20150920” is associated with this decoy, which is a week prior to media articles announcing that the Crown Price of Thailand Maha Vajiralongkorn will lead the Bike for Dad 2015 event. At first, we believed the use of the Bike for Dad 2015 event was unrelated to the previous Erawin Shine bombing decoys. According to the same announcement article, the Crown Prince said that the bike route would pass the Ratchaprasong intersection, which is where the Erawin Shine bombing took place. Therefore, the threat actors using this within their social engineering attempts continues to follow the theme involving the bombing of the shrine in Bangkok, as it is undoubtedly still in the hearts and minds of the Thai people.

The final remaining known decoy includes photos of Chitpas Tant Kridakon (Figure 7), who is known as heiress to the largest brewery in Thailand. Chitpas is heavily involved with Thailand politics and was a core leader of the People’s Committee for Absolute Democracy (PCAD), which is an organization that staged anti-government campaigns in 2013 and 2014. As recently as September 2015, Chitpas has been in the news for her attempts to become an officer in the Royal Thai Police force, which has caused protests due to her political stance. Two of the images in the slideshow can be seen in an article that was published on September 20, 2015. These images were associated with the Bookworm campaign code “20150905”.

By comparing the campaign codes with the dates of known attacks or the date of the events shown in the decoys, we found that the campaign codes precede the attack or event dates by 6 to 18 days. The campaign code date preceding the attack or associated events suggests that the threat actors perform development operations on their tools and then choose their decoy. These decoy documents also suggest that the threat actors actively track current news events and use photographs from the media to create their decoy slideshows.

Compromised Hosts

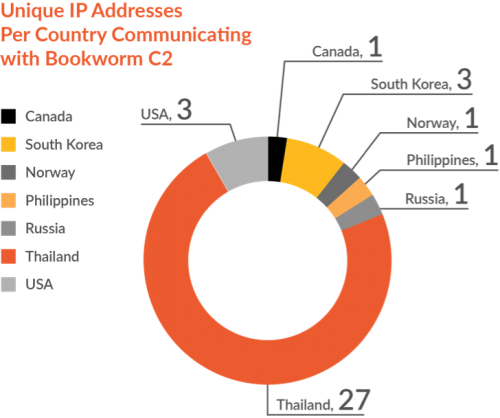

Unit 42 analyzed the systems communicating with the Bookworm C2 domains and found that a majority of the IP addresses existed within autonomous systems (ASN) located in Thailand. The pie chart in Figure 8 shows that the vast majority (73%) of the hosts are geographically located in Thailand, which matches the known targeting of this threat group. We believe that the IP addresses from Canada, Russia and Norway are analysis systems of antivirus companies or security researchers. The IP addresses in South Korea prove interesting and could suggest that this threat group has carried out an attack campaign on targets in locale as well. However, we’ve found no additional evidence to corroborate this theory.

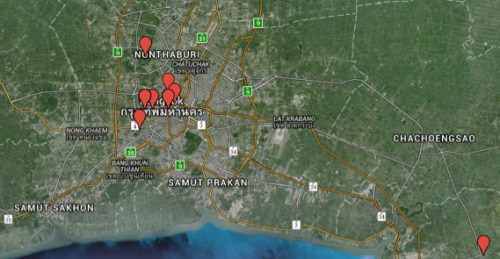

We took the IP addresses seen communicating with Bookworm C2 servers and obtained their geographic coordinates using an IP geolocation database and plotted them on a map, as seen in Figure 9. A majority of the IP addresses in Thailand have coordinates in the Bangkok metropolitan area, with one in the southern town of Pattini and one in the Phanat Nikhom District of the Chonburi Province. IP geolocation systems are not perfectly accurate, but the data suggests that most of the compromised hosts exist near the largest city of Bangkok. This grouping of compromised hosts also aligns with the known targeting, as Bangkok and Nonthaburi is where a majority of the government of Thailand exists.

Bookworm’s Threat Infrastructure

Bookworm-related infrastructure created by threat actors mainly involves the use of dynamic domains, however, an early sample used a fully qualified domain name (FQDN) owned by the actor. The actors also appear to have access to legitimate servers that they use to host Bookworm and other related tools for attacks. Overall, the Bookworm infrastructure overlaps with the infrastructure hosting C2 servers used by various attack tools, including FFRAT, Poison Ivy, PlugX, and others.

Compromised Web Servers

Unit 42 has seen threat actors hosting Bookworm and other related tools on legitimate websites, which suggests the actors have unauthorized access to these servers. We have witnessed Bookworm samples hosted on a website belonging to the following organizations:

- Two branches of government in Thailand

- Thai Military

- A Taiwanese Labor Association

Three of the four compromised webservers have been breached in the past with each being listed on Zone-h as being defaced, while the remaining site was defaced by the TURKHACKTEAM, according to a Google cache from November 11, 2015. The specific details of how the actors gained access to these sites is unclear, however, one site has a publicly accessible form that would allow visitors to upload files to the webserver (Figure 8). Unit 42 believes that threat actors could have uploaded Bookworm to this server using this form. It is also possible that the threat actors uploaded an ASP shell to gain further control over this webserver. We also speculate that these threat actors may use strategic web compromises (SWC) as an attack vector in future campaigns using their unauthorized access to webservers.

The site hosting this file upload form belongs to one of the organizations targeted with Bookworm. This may suggest that the threat actors used this webserver to pivot from the webserver into the internal network.

Infrastructure Overlap and Related Tools

The domains hosting Bookworm C2 servers (see Indicators of Compromise section of our Bookworm blog) connect to a larger infrastructure that the threat actors are using to host C2 servers for other tools in their toolset. So far, Unit 42 has seen infrastructure overlaps with servers hosting C2 servers for samples of the FFRAT, PlugX, Poison Ivy and Scieron Trojans, suggesting that the threat actors use these tools as the payload in their attacks.

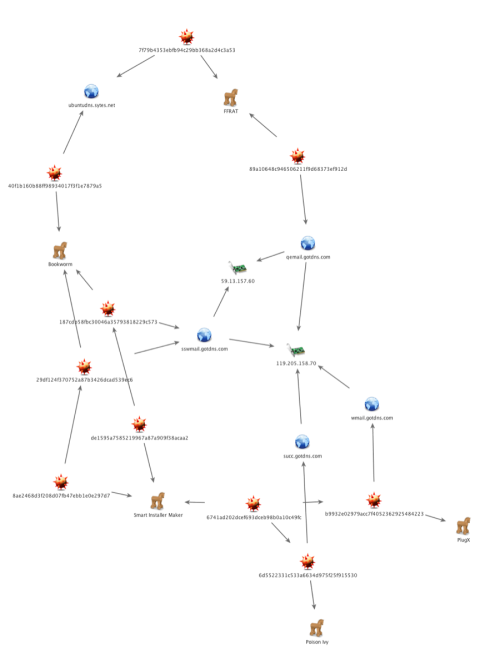

Unit 42 enumerated the threat infrastructure related to Bookworm and created a chart to visualize connected entities to its current attack campaign. The infrastructure is fairly complex and has many overlaps with other toolsets. Figure 11 below shows a fraction of the threat infrastructure that visualizes a connection between Bookworm, FFRAT, PlugX and Poison Ivy.

The overlap between Bookworm, PlugX and Poison Ivy samples involves the use of the Smart Installer Maker, which is a common technique used by this threat group. In one particular case, a sample of the Smart Installer Maker (MD5: 6741ad202dcef693dceb98b0a10c49fc) installed both a PlugX and Poison Ivy Trojan that communicated with domains that resolved to an IP address (119.205.158.70) that also resolved a Bookworm C2 domain (sswmail.gotdns[.]com). This IP address was also used to resolve a domain (qemail.gotdns[.]com) that actors used to host a C2 server for another Trojan known as FFRAT. We observed another direct overlap in a C2 domain (ubuntudns.sytes[.]net) used for both Bookworm and FFRAT.

As previously mentioned, the infrastructure related to Bookworm is fairly complex with many connections to domains hosting C2 servers for other tools. The related infrastructure and associated malware can be seen in the table below.

| Domain | Malware Family/Cluster |

| web12.nhknews[.]hk | Bookworm |

| systeminfothai.gotdns[.]ch | Bookworm |

| bkmail.blogdns[.]com | Bookworm |

| thailandbbs.ddns[.]net | Bookworm |

| blog.nhknews[.]hk | Bookworm |

| news.nhknews[.]hk | Bookworm |

| sysnc.sytes[.]net | Bookworm |

| debain.servehttp[.]com | Bookworm |

| sswmail.gotdns[.]com | Bookworm |

| sswwmail.gotdns[.]com | Bookworm |

| ubuntudns.sytes[.]net | Bookworm, FFRAT |

| linuxdns.sytes[.]net | Bookworm, FFRAT |

| www.chinabztech[.]com | FFRAT |

| www.tibetonline[.]info | FFRAT |

| 3h01.dwy[.]cc | FFRAT |

| www.vxea[.]com | FFRAT |

| bdimg.s.dwy[.]cc | FFRAT |

| nine.alltosec[.]com | FFRAT |

| www.rooter[.]tk | FFRAT |

| wucy08.eicp[.]net | FFRAT |

| welcome.dnsd[.]info | FFRAT |

| www.ifilmone[.]com | FFRAT |

| pcal2.dwy[.]cc | FFRAT |

| luotuozhizhu.blog.163[.]com | FFRAT |

| office.alltosec[.]com | FFRAT |

| ftpseck.ftp21[.]net | FFRAT |

| wuzhiting.3322[.]org | FFRAT |

| qemail.gotdns[.]com | FFRAT |

| googleupdating[.]com | FFRAT |

| welcometohome.strangled[.]net | FFRAT |

| zz.alltosec[.]com | FFRAT |

| back.rooter[.]tk | FFRAT |

| products.alltosec[.]com | FFRAT |

| windowsupdating[.]net | FFRAT |

| app.rooter[.]tk | FFRAT |

| hkemail.f3322[.]org | FFRAT |

| pcal2.yahoolive[.]us | FFRAT |

| happy.tftpd[.]net | PlugX |

| weather.webhop[.]me | PlugX |

| ns1.vancouversun[.]us | PlugX |

| n5579a.voanews[.]hk | PlugX |

| hope.jumpingcrab[.]com | PlugX |

| news.nowpublic[.]us | PlugX |

| web.vancouversun[.]us | PlugX |

| news.voanews[.]hk | PlugX |

| bugatti.from-wa[.]com | PlugX |

| web.voanews[.]hk | PlugX |

| ns3.yomiuri[.]us | PlugX |

| tree.crabdance[.]com | PlugX |

| supercat.strangled[.]net | PlugX |

| webupdate.strangled[.]net | PlugX |

| breaknews.mefound[.]com | PlugX |

| succ.gotdns[.]com | Poison Ivy, PlugX |

| imail.gotdns[.]com | Poison Ivy, PlugX |

| wmail.gotdns[.]com | Poison Ivy, PlugX |

| xxcase.gotdns[.]com | Poison Ivy |

| romadc.homelinux[.]com | Poison Ivy |

| 3389temp.dyndns[.]org | Poison Ivy |

| ahcase.gotdns[.]com | Poison Ivy |

| kcase.gotdns[.]com | Poison Ivy |

| 3389pi.servegame[.]org | Poison Ivy |

| flashcard.gotdns[.]com | Poison Ivy |

| kr-update.homelinux[.]com | Poison Ivy |

| 3389.homeunix[.]org | Poison Ivy |

| flashgame.gotdns[.]com | Poison Ivy |

| anhei.gotdns[.]com | Poison Ivy |

| xcase.gotdns[.]com | Poison Ivy |

| education.suroot[.]com | Scieron |

| server.organiccrap[.]com | Scieron |

| pricetag.deaftone[.]com | Scieron |

| apple.dynamic-dns[.]net | Scieron |

| williamsblog.dtdns[.]net | Scieron |

| will-smith.dtdns[.]net | Scieron |

| durant.dumb1[.]com | Scieron |

Table 2 Threat Infrastructure Related to Bookworm

We made connections between domains seen in Table 2 through shared stolen code signing certificates, other PE build commonalities, passive DNS data and direct C2 domain overlap. The domains connected using passive DNS all share common IP addresses used to resolve the domain. The following IP addresses provided many of the connection points within the infrastructure via passive DNS overlap:

- 103.226.127.47

- 104.156.239.105

- 112.167.143.179

- 115.144.107.22

- 115.144.107.46

- 115.144.107.52

- 115.144.107.53

- 115.144.107.134

- 115.144.166.209

- 119.205.158.70

- 43.248.8.249

Conclusion

Threat actors have targeted the government of Thailand and delivered the newly discovered Bookworm Trojan since July 2015. The actors appear to follow a set playbook, as the observed TTPs are fairly static within each attack in this campaign. The threat actors have continually used Flash Player installers and Flash slideshows for decoys. The decoy slideshows all contain photos from very meaningful events to individuals in Thailand, suggesting that the actors continually look for impactful events to use to disguise their attacks.

The vast majority of systems communicating with Bookworm C2 servers are within the Bangkok metropolitan area where a majority of the government of Thailand exists. While the current campaign has targeted the Thai government, Unit 42 believes the threat actors will target other governments to deliver Bookworm in future campaigns.

Get updates from

Palo Alto

Networks!

Sign up to receive the latest news, cyber threat intelligence and research from us

By submitting this form, you agree to our Terms of Use and acknowledge our Privacy Statement.